Narrative: 1990s: New Musical Trends

The number of Dominicans in the United States doubled in the 1990s, from slightly over half a million to over one million by the year 2000. This aggressive demographic growth transformed the Dominican community in the United States, making them the fourth-largest Hispanic/Latino group in the country, after Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans. This population growth gave rise to an intense internal mobility among Dominicans. The number of Dominicans increased significantly within states with large pre-existing Dominican communities such as New York, New Jersey, Florida, and Massachusetts, as well as in other states with smaller Dominican populations such as Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Arizona, and Hawaii.

"In 1990, more babies of Dominican descent were born in the Bronx than in any other borough..."

Demographic growth also generated geographic shifting. In New York City, home to the largest Dominican concentration for the last four decades, the Bronx began to emerge as a strong contender to Manhattan, a borough that had historically housed the largest Dominican population. In 1990, more babies of Dominican descent were born in the Bronx than in any other borough. This particular pattern would hold true for the next two decades, making the Bronx the borough with the largest Dominican population by far. During this decade, while new Dominican communities budded throughout the United States, older Dominican settlements matured and achieved higher levels of integration into mainstream U.S. society. In the Northeast, for instance, Guillermo Linares of New York City, New York, and Key Palacios of Englewood, New Jersey, were the first people of Dominican ancestry to be elected to City Council seats in the United States. The former, an immigrant, and the latter, U.S. born.

As their community matured and grew, Dominican cultural contributions to U.S. society would become more visible, particularly through music. In the 1990s, for instance, second generation Dominicans expanded on the contributions of early Dominican musicians, offering contemporary interpretations of classic rhythms such as merengue and bachata. This decade saw the birth and boom of merengue house, the popularization of bachata, and the emergence of urban bachata, along with the music of Oro Sólido, all spearheaded by people of Dominican descent.

"This decade saw the birth and boom of merengue house..."

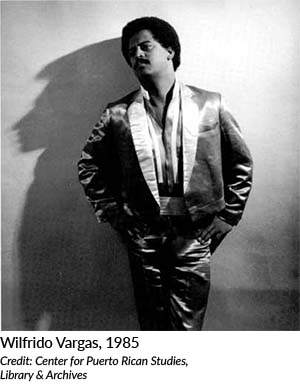

In the 1990s, a variety of musical styles that combined merengue with different genres such as hip-hop, reggae, techno, dancehall, and rap emerged. Merengue House,[1] for instance, a new genre that combined merengue, electronics, and rap, follows in the footsteps of House and Latin House, two musical styles that developed in the U.S. in the 1980s. While House music, spearheaded by African Americans, mixed electronics with traditional African American rhythms and sounds such as R&B, disco, funk, and soul, Latin House fuses Latin and Latin American music with electronic music. In the U.S., Puerto Ricans spearheaded Latin House music. In the Dominican Republic, Wilfrido Vargas’ 1984 hit “El Jardinero,” experimented with the mixing of merengue, electronics, and rap.[2]

In the 1990s, a variety of musical styles that combined merengue with different genres such as hip-hop, reggae, techno, dancehall, and rap emerged. Merengue House,[1] for instance, a new genre that combined merengue, electronics, and rap, follows in the footsteps of House and Latin House, two musical styles that developed in the U.S. in the 1980s. While House music, spearheaded by African Americans, mixed electronics with traditional African American rhythms and sounds such as R&B, disco, funk, and soul, Latin House fuses Latin and Latin American music with electronic music. In the U.S., Puerto Ricans spearheaded Latin House music. In the Dominican Republic, Wilfrido Vargas’ 1984 hit “El Jardinero,” experimented with the mixing of merengue, electronics, and rap.[2]

"Proyecto Uno is an internationally recognized merengue house group that emerged in New York City’s East Side in 1989..."

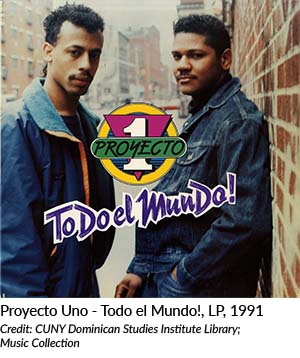

Proyecto Uno is an internationally recognized merengue house group that emerged in New York City’s East Side in 1989 under the leadership of Nelson Zapata. The group emerged from Zapata’s desire to engage intimately with merengue, which he affectionately regarded as “the music of [his] country.”[3] Zapata, born in the Dominican Republic, grew up in New York City. Prior to Proyecto Uno, Zapata had experimented with other merengue groups but it was Zapata’s association with Rick Echavarría and Pavel de Jesús that really paid off when the trio co-founded Proyecto Uno, a group that would go on to amass a large following, extending from their native New York City to Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Their popularity gave rise to the merengue house movement.

Proyecto Uno is an internationally recognized merengue house group that emerged in New York City’s East Side in 1989 under the leadership of Nelson Zapata. The group emerged from Zapata’s desire to engage intimately with merengue, which he affectionately regarded as “the music of [his] country.”[3] Zapata, born in the Dominican Republic, grew up in New York City. Prior to Proyecto Uno, Zapata had experimented with other merengue groups but it was Zapata’s association with Rick Echavarría and Pavel de Jesús that really paid off when the trio co-founded Proyecto Uno, a group that would go on to amass a large following, extending from their native New York City to Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Their popularity gave rise to the merengue house movement.

Given Zapata’s extensive experience with traditional merengue, Proyecto Uno’s first songs remained within the limits of the genre. The group began developing its own sound when Zapata suggested to de Jesus the idea of combining house music with merengue. De Jesus, a childhood friend from Santo Domingo, was the first of Proyecto Uno’s members to move to New York City from the Dominican Republic. During this time, de Jesus worked at Quad Recording Studios in Midtown Manhattan, where artists like Whitney Houston, The Ramones, U2, and Mick Jagger were known to record. He served as the recording assistant and sound engineer for Grammy-award winning house music legends David Morales and Frankie Knuckles.

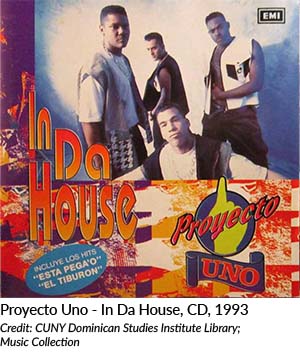

Proyecto Uno’s first hit, “Todo el Mundo” (click here to listen) is a typical representation of merengue house. Other hits would follow such as “Brinca,” (click here to listen) “Esta Pegao,” (click here to listen) and “El Tiburon” (click here to listen). “El Tiburon” was the only Spanish-language song, from the album Da House, featured on JAM’N 94.5, a hip-hop radio station in Boston. The song also became popular in Boston’s non-Latin nightclubs.[4] Similarly, by this time, Dick Scott, who also managed Boys II Men, New Kids on the Block, and New Edition, managed Proyecto Uno.[5]

Proyecto Uno’s first hit, “Todo el Mundo” (click here to listen) is a typical representation of merengue house. Other hits would follow such as “Brinca,” (click here to listen) “Esta Pegao,” (click here to listen) and “El Tiburon” (click here to listen). “El Tiburon” was the only Spanish-language song, from the album Da House, featured on JAM’N 94.5, a hip-hop radio station in Boston. The song also became popular in Boston’s non-Latin nightclubs.[4] Similarly, by this time, Dick Scott, who also managed Boys II Men, New Kids on the Block, and New Edition, managed Proyecto Uno.[5]

Over the years, Proyecto Uno transformed from a Dominican-only band into one that included two members of Puerto Rican ancestry: Erik Morales and Johnny Salgado. The group also included Magic Juan, a Washington Heights born Dominican, raised in New Jersey, reflecting the internal mobility characterizing Dominican communities at the time. The addition of Puerto Ricans to the band continues a tradition of Latino-intermingling present in early Dominican U.S.-based musical groups. Proyecto Uno earned many awards, including two Orquídea awards in Venezuela (1993 and 1995), and a Latin Billboard (1997) and two Emmy awards (1997 and 1999) in the U.S.

"The addition of Puerto Ricans to the band continues a tradition of Latino-intermingling present in early Dominican U.S.-based musical groups..."

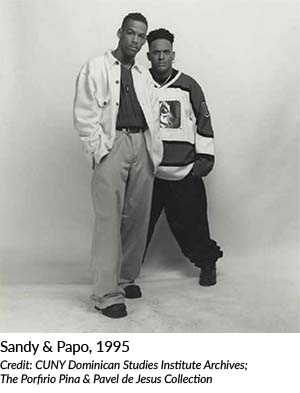

In 1992, along their ascent to superstardom, Proyecto Uno’s founding members, Nelson Zapata and Pavel de Jesús spread merengue house further by forming a new group: Sandy y Papo.[6] Long-time friends who were heavily involved in the hip-hop scene in their native Dominican Republic Sandy Carriello "Sandy MC" and Luis Deschamps “MC Papo,” would go on to become central figures in the merengue house movement that emerged in New York City.[7] Their discography includes Sandy y Papo MC (1995), Otra Vez (1997), and The Remix Album (1998), among others. One of their biggest hits was “El Mueve Mueve” (I Like to Move It) (click here to listen). The lyrics of this song are performed in rap style all throughout the piece. “Huelepega,” another of their hits, is a song that served to promote a Venezuelan film of the same name. Besides the inclusion of English and rap styles in their lyrics, their overall aesthetic was also influenced by New York hip-hop artists.

In 1992, along their ascent to superstardom, Proyecto Uno’s founding members, Nelson Zapata and Pavel de Jesús spread merengue house further by forming a new group: Sandy y Papo.[6] Long-time friends who were heavily involved in the hip-hop scene in their native Dominican Republic Sandy Carriello "Sandy MC" and Luis Deschamps “MC Papo,” would go on to become central figures in the merengue house movement that emerged in New York City.[7] Their discography includes Sandy y Papo MC (1995), Otra Vez (1997), and The Remix Album (1998), among others. One of their biggest hits was “El Mueve Mueve” (I Like to Move It) (click here to listen). The lyrics of this song are performed in rap style all throughout the piece. “Huelepega,” another of their hits, is a song that served to promote a Venezuelan film of the same name. Besides the inclusion of English and rap styles in their lyrics, their overall aesthetic was also influenced by New York hip-hop artists.

In 1999, Sandy y Papo ended when Luis Deschamps (MC Papo) died in a car accident on his way to the Santo Domingo airport. This tragedy occurred just four months after the duo debuted as the first merengue house group at the Viña del Mar International Song Festival in Chile, and before they were set to begin touring Venezuela and Spain.[8] Sandy MC continued as a solo artist and achieved success with the song “Homenaje a Papo.” He also worked on new productions during the first decade of the 2000s. In 2006, the Australian animated film Happy Feet included parts of the song “Candela” previously recorded by the group.

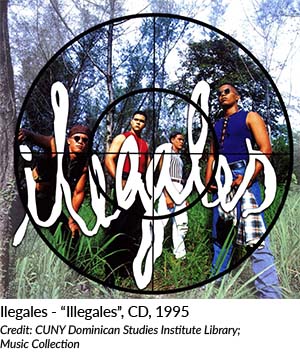

Los Ilegales is a Grammy-nominated merengue house group formed by leading singer-songwriter Vladimir Dotel in 1995.[9] Other early members of the group include Manuel Tejada, Roger Sanchez',[10] and Victor Waill, who prior to joining the band worked as a vocalist for Wilfrido Vargas.[11] One of the longest lasting merengue house ensembles, the group has recorded 13 albums including Ilegales (1995), Rebotando (1997), El Sonido en Vivo (2014), and Inagotable (2016). Some of their most internationally renowned hits are “La Morena,” (click here to listen) “El Taqui Taqui,” (click here to listen) and “Rebotando” (click here to listen). Like Proyecto Uno and Sandy y Papo, Los Ilegales were readily embraced by a growing a large, loyal base-fans in both the United States and Latin America, especially in Venezuela, Chile, and Ecuador.

Los Ilegales is a Grammy-nominated merengue house group formed by leading singer-songwriter Vladimir Dotel in 1995.[9] Other early members of the group include Manuel Tejada, Roger Sanchez',[10] and Victor Waill, who prior to joining the band worked as a vocalist for Wilfrido Vargas.[11] One of the longest lasting merengue house ensembles, the group has recorded 13 albums including Ilegales (1995), Rebotando (1997), El Sonido en Vivo (2014), and Inagotable (2016). Some of their most internationally renowned hits are “La Morena,” (click here to listen) “El Taqui Taqui,” (click here to listen) and “Rebotando” (click here to listen). Like Proyecto Uno and Sandy y Papo, Los Ilegales were readily embraced by a growing a large, loyal base-fans in both the United States and Latin America, especially in Venezuela, Chile, and Ecuador.

"Los Ilegales were readily embraced by a growing a large, loyal base-fans in both the United States and Latin America..."

In January of 1998, Los Ilegales band member, José Fermín González, more commonly known as Jason, died after a car accident in Santo Domingo. He spent a month in the intensive care unit at Hospital Central de las Fuerzas Armadas y la Policía, during which time he was visited by the President of the Dominican Republic, Dr. Leonel Fernández Reyna, in recognition of Fermín González’s popularity, high esteem among Dominicans, and contributions to Dominican music.[12] In recent years, Los Ilegales have had the opportunity to collaborate with Dominican urban artist, Vakeró, and Dominican merengue legend, Johnny Ventura.

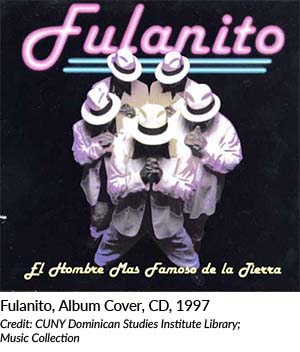

Musical group Fulanito has made one of the most pivotal contributions to the merengue house genre. They have sold over 5 million albums worldwide and have placed on Latin music charts in countries around the world, including Japan, Switzerland, the United States, and Chile. One of the secrets of their success lies in the unique foresight held by the group’s founding members, Rafael “Dose” Vargas and Winston de la Rosa, in creating a new rhythm that delighted and challenged both the elders and the young.

Musical group Fulanito has made one of the most pivotal contributions to the merengue house genre. They have sold over 5 million albums worldwide and have placed on Latin music charts in countries around the world, including Japan, Switzerland, the United States, and Chile. One of the secrets of their success lies in the unique foresight held by the group’s founding members, Rafael “Dose” Vargas and Winston de la Rosa, in creating a new rhythm that delighted and challenged both the elders and the young.

"Fulanito decided to center its music on merengue típico, diverting from the precedent set by merengue house pioneers Proyecto Uno..."

Fulanito decided to center its music on merengue típico, diverting from the precedent set by merengue house pioneers Proyecto Uno. De la Rosa’s father, the legendary merengue accordionist Arsenio de la Rosa, likely inspired Fulanito’s new music style. Born in El Cibao, the heartland of the Dominican Republic and the site where merengue típico originates, de la Rosa senior was a third generation accordion master who experienced first-hand the development of merengue: from its marginalized position in the Dominican countryside to its internal popularization and international explosion, with the rise and fall of dictator Rafael L. Trujillo.[13] While music had always been central to his life, maestro de la Rosa admitted to the Miami New Times that after moving to New York at the age of 21, he had to give music up “because it didn’t pay anymore.”[14] Everything changed for him when 36 years later, his son, Winston de la Rosa, asked him to go to the recording studio and play his merengue beat with his accordion over a rap song. That song was “Guayando,” which, as Karl Ross says, “was so arresting that DJs on Spanish-language radio stations such as Miami's El Zol 95.7 (WXBJ-FM) would play it several times in a row.”[15] “Guayando” (click here to listen) achieved commercial success and sealed Fulanito’s musical career forever. By this time, maestro de la Rosa regularly accompanied his son, achieving superstardom fame too, and was deservingly titled in time El Maestro del Acordeon.

Fulanito scored several hit singles on both Billboard's tropical/salsa and hot Latin tracks charts with songs such as “El Cepillo” and “La Novela” while their full-length albums Hombre Más famoso de la tierra (1997) and El Padrino (1999) have been very popular. The group has been the recipient of various Premios ACE[16] for Outstanding Band (1999); for Impact Band of the Year (1998); and for Outstanding Latin Group (1997). They have also received a Premio GLOBO (1999) for Tropical Merengue Best Típico-House Group. In addition, Fulanito received a nomination for Artista Tropical Salsa del Año by Premio Lo Nuestro a la Música Latina (1999). Fulanito has also received two Grammy award nominations, one for El Padrino in the category of Best Merengue Album (2000) and another for Vacaneria! in the category of Best Latin Urban Album in 2007.[17]

"Fulanito’s success with their innovative típico sound would go on to inspire a new generation..."

Fulanito’s success with their innovative típico sound would go on to inspire a new generation of merengue house musicians such as Sancocho, Nueve Once (911), and Kinito Mendez, who taking after Fulanito, combined other Dominican folkloric genres, including bachata and palos. Rafael Vargas, explained the group’s success as “both a vindication for maestro Arsenio de la Rosa’s [music] … and as a unifying force among Dominican immigrants, serving as a reminder of their country roots, particularly for their U.S.-born offspring.”[18]

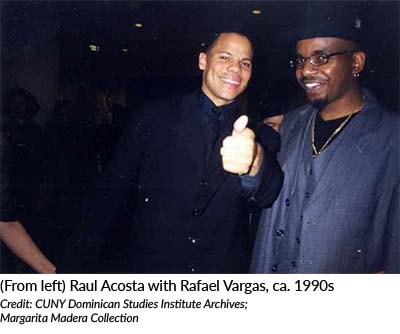

In the meantime, while merengue house was curving what would prove to be a very successful trajectory with several renowned artists, a parallel new music began to emerge, that of Oro Sólido. In 1994, Dominican born and Jersey City raised Raul Acosta introduced a new style of merengue with his band Oro Sólido. According to Nelson Santana, “Acosta’s merengues were rhythmically more upbeat and placed less importance on vocals.[19] In addition, [Oro Sólido used] a lower pitched saxophone [baritone saxophone], making this instrument a protagonist among the instruments used in the song.”[20] The success of Oro Sólido with hits like “Ta Cache” (click here to listen) and “Abusadora” (click here to listen) gave rise to other merengue groups during the decade such as Soberbia and Oro Duro, among others.

In the meantime, while merengue house was curving what would prove to be a very successful trajectory with several renowned artists, a parallel new music began to emerge, that of Oro Sólido. In 1994, Dominican born and Jersey City raised Raul Acosta introduced a new style of merengue with his band Oro Sólido. According to Nelson Santana, “Acosta’s merengues were rhythmically more upbeat and placed less importance on vocals.[19] In addition, [Oro Sólido used] a lower pitched saxophone [baritone saxophone], making this instrument a protagonist among the instruments used in the song.”[20] The success of Oro Sólido with hits like “Ta Cache” (click here to listen) and “Abusadora” (click here to listen) gave rise to other merengue groups during the decade such as Soberbia and Oro Duro, among others.

"In 1994, Dominican born and Jersey City raised Raul Acosta introduced a new style of merengue with his band Oro Sólido..."

Taking place concurrently with the boom of merengue house and the rhythm introduced by Oro Sólido, came the popularization of bachata, a 1960s guitar-based music created by the Dominican rural working class. It is known for its raw vocals, simple instrumentation, and often double entendre lyrics, which typically revolves around heartbreak, betrayal, and longing of a romantic nature. Given its associations with the least economically advantaged classes, bachata was systematically confined to the margins of Dominican society for nearly three decades. Yet, bachata had its followers among Dominicans who attended live performances, danced to the tunes, bought LPs, and tuned in via radio to listen to bachata music. Bachata became widely spread with two major events: mass migration of Dominicans to the U.S. and the rise of Juan Luis Guerra.

"...bachata had its followers among Dominicans who attended live performances, danced to the tunes, bought LPs, and tuned in via radio..."

Despite the stigma placed upon bachata by the upper economic classes of Dominican society, the rest did not give an iota about the devalorization of bachata, and among those who migrated to the U.S. there were plenty of faithful bachateros who longed for this music. In the U.S., Dominican migrants created a new market for bachata. Their interest in the music came not only from their pre-existing relationship to it, but also because now, in a foreign land, bachata transformed into a symbol that reminded them of home. In addition, bachata, which is also known as “musica de amargue,”[21] or "music of heartbreak,” accurately captured and expressed the feelings of sadness, melancholy, pain, and anguish experienced by migrants, particularly when entering a society that “neither needed nor wanted them”.[22]

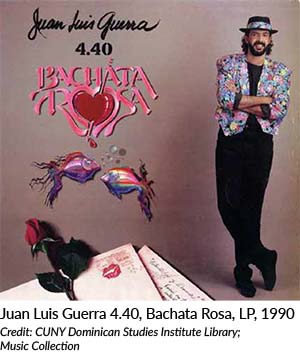

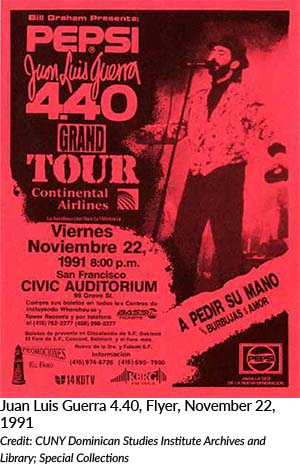

Bachata’s popularity was heightened in 1990, with the release of classically trained Dominican musician, Juan Luis Guerra y 4.40’s groundbreaking album: Bachata Rosa. Released 8 years after his graduation from the Berklee College of Music in Boston, Bachata Rosa was praised for its flowery lyricism, polished instrumentation, and high-quality studio production.[23] In the Dominican Republic, this album marked a turning point for bachata. From this moment onward, the genre’s popularity would extend beyond Dominican working class sectors, and gain favor with the middle and upper classes. It is important to recognize, however, that to this day there are still social sectors in the Dominican Republic, including among the elite, that reserve some contempt for the genre.

Bachata’s popularity was heightened in 1990, with the release of classically trained Dominican musician, Juan Luis Guerra y 4.40’s groundbreaking album: Bachata Rosa. Released 8 years after his graduation from the Berklee College of Music in Boston, Bachata Rosa was praised for its flowery lyricism, polished instrumentation, and high-quality studio production.[23] In the Dominican Republic, this album marked a turning point for bachata. From this moment onward, the genre’s popularity would extend beyond Dominican working class sectors, and gain favor with the middle and upper classes. It is important to recognize, however, that to this day there are still social sectors in the Dominican Republic, including among the elite, that reserve some contempt for the genre.

"Bachata Rosa’s success paved the way for many other established bachateros to travel to New York City..."

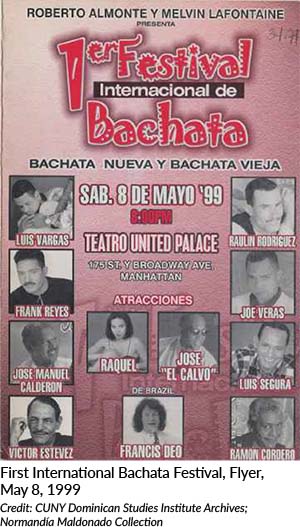

Shortly after Bachata Rosa was released, the album became an international success selling over five million copies worldwide, receiving a Grammy for Best Tropical Latin Album, and winning two Premios Lo Nuestro, for Tropical Album of the Year and for Tropical Group of the Year (click here to listen to recordings 1,2, and 3). Bachata Rosa’s success paved the way for many other established bachateros to travel to New York City and other parts of the U.S. to perform for Dominicans and the greater Latino community as well. The wide acceptance of bachata was captured in Santo Domingo Blues, a documentary that highlights the history of bachata and its significance to the Dominican community abroad in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[24]

Shortly after Bachata Rosa was released, the album became an international success selling over five million copies worldwide, receiving a Grammy for Best Tropical Latin Album, and winning two Premios Lo Nuestro, for Tropical Album of the Year and for Tropical Group of the Year (click here to listen to recordings 1,2, and 3). Bachata Rosa’s success paved the way for many other established bachateros to travel to New York City and other parts of the U.S. to perform for Dominicans and the greater Latino community as well. The wide acceptance of bachata was captured in Santo Domingo Blues, a documentary that highlights the history of bachata and its significance to the Dominican community abroad in the late 1990s and early 2000s.[24]

"Los Tinellers mixed traditional bachata with U.S. rhythm and blues (R&B)—giving rise to a cosmopolitan version of the genre..."

Bachata was given new life in 1993, when a new group, Los Tinellers (The Teenagers), emerged. Though Los Tinellers Lenny, Anthony “Romeo,” and Sammy did not achieve notoriety in the music scene, the group laid the foundation that would give rise, in 1999, to the phenomenon that is Aventura: Lenny, Romeo, Henry, Max “Mikey.”[25] Following in the footsteps of merengue house artists, Los Tinellers mixed traditional bachata with U.S. rhythm and blues (R&B)—giving rise to a cosmopolitan version of the genre, today known as urban bachata. Within just a few years’ time, this experimentation transformed the group, now properly called Aventura, into a musical sensation, and eventually, one of the most successful music groups in the history of Dominican/Latino music in the U.S.

Bachata was given new life in 1993, when a new group, Los Tinellers (The Teenagers), emerged. Though Los Tinellers Lenny, Anthony “Romeo,” and Sammy did not achieve notoriety in the music scene, the group laid the foundation that would give rise, in 1999, to the phenomenon that is Aventura: Lenny, Romeo, Henry, Max “Mikey.”[25] Following in the footsteps of merengue house artists, Los Tinellers mixed traditional bachata with U.S. rhythm and blues (R&B)—giving rise to a cosmopolitan version of the genre, today known as urban bachata. Within just a few years’ time, this experimentation transformed the group, now properly called Aventura, into a musical sensation, and eventually, one of the most successful music groups in the history of Dominican/Latino music in the U.S.

[1] Referred to also as Merengue Rap or Merenrap in some scholarly, journalistic articles, as well as on playlists on various platforms. See for instance Hip Hop around the World: An Encyclopedia by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith and Anthony J. Fonseca. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2018, 471; and “A Look Back at Merenhouse, the Most Lit Pari Music of All Time,” by Veronica Bayetti Flores, Remezcla.com, 17 December, 2017, https://remezcla.com/lists/music/merenhouse-merenrap-tribute/. Accessed December 30, 2019.

[2] Lipsitz, George. Footsteps in the Dark: the Hidden Histories of Popular Music. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007, 145.

[3] Sellers, Julie A. Merengue and Dominican Identity: Music as National Unifer. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2004, 177

[4] Valdes, Alisa. “On the Beat: How Proyecto Uno Is Working to Be the Next Big Thing.” The Boston Globe, Sunday City Edition [Online] 25 February 1996, B34. Newspapers.com.

[5] Valdes, "On the Beat," B34.

[6] “Biografía de Sandy y Papo.” Buena Música, 2019, https://www.buenamusica.com/sandy-y-papo/biografia. Accessed 27 August, 2019.

[7] “VIVA RAP 89.” Espacio Urbano Cultural Dominicano, 20 July 2008, http://espacioucd.blogspot.com/2008/07/viva-rap-89.html. Accessed 27 August, 2019.

[8] “Luis E. Dechamps, 23, Dominican Rap Star 'Papo.'” Sun Sentinel, 14 July 1999, https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1999-07-14-9907140162-story.html. Accessed 27 August 2019.

[9] “Vladimir Dotel: ‘Este es un trabajo serio y constante, hay que trabajar muy duro.’” Diario Libre, 22 September 2013, https://www.diariolibre.com/revista/vladimir-dotel-este-es-un-trabajo-serio-y-constante-hay-que-trabajar-muy-duro-DMDL403246. Accessed 27 August 2019.

[10] Bush, John. “Ilegales.” AllMusic, RhythmOne, 2019, https://www.allmusic.com/artist/ilegales-mn0000071018/biography. Accessed on 27 August, 2019.

[11] Rivera, Severo. “Víctor Waill dejó su impronta en la salsa, el merengue y la bachata.” Diario Libre, 7 September 2019, https://www.diariolibre.com/revista/musica/victor-waill-dejo-su-impronta-en-la-salsa-el-merengue-y-la-bachata-NA13315976. Accessed 27 August 2019.

[12] “Murió cantante de Los Ilegales.” La Nación, 15 January 1998, https://www.nacion.com/el-pais/murio-cantante-de-los-ilegales/FBYGB2WZZNADHFTWOYJYXRYIPQ/story/. Accessed 27 August 2019.

[13] Hutchinson, Sydney. Merengue Típico in Transnational Dominican Communities: Gender Geography Migration and Memory in a Traditional Music, 2008. New York University, PhD Dissertation, 1.

[14] Ross, Karl. “The Dominican Squeezebox Goes Digital.” Miami New Times, 6 April, 2000, https://www.miaminewtimes.com/music/the-dominican-squeezebox-goes-digital-6356376. Accessed 27 August 2019.

[15] Ross, "The Dominican Squeezebox"

[16] Association of Entertainment Critics of New York

[17] “Fulanito’s GRAMMY Awards history.” Grammy.com, 2019, https://www.grammy.com/grammys/artists/fulanito. Accessed 27 August, 2019.

[18] Ross, “The Dominican Squeezebox”

[19] Santana, Nelson. “Expanding the Scope of Music: From Dancing Tunes to Production.” In “Dominican Immigrants” by Ramona Hernández and Anthony Stevens-Acevedo. In Multicultural America: An Encyclopedia of the Newest Americans Vol. I., edited by Ronald H. Bayor. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2011, 513-516.

[20] Santana, "Expanding the Scope," 514.

[21] Some have translated amargue to bitterness which is a literal translation. Yet, amargue reflects a deep sadness and emotional pain and suffering because of love.

[22] Hernández, Ramona. The Mobility of Workers under Advanced Capitalism: Dominican Migration to the United States. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002, 85.

[23] Small, Mark. “Juan Luis Guerra: Tropical Music Superstar.” Berklee Today, Berklee College of Music, 2004, https://www.berklee.edu/bt/171/coverstory.html. Accessed on 27 August, 2019.

[24] Santo Domingo Blues. Directed by Alex Wolfe, performances by Luis Vargas, Raulín Rodríguez, Eladio Romero Santos, Aridia Ventura, Teodoro Reyes, Yoan Soriano, Luis Segura, Ramón Cordero, José Manuel Calderón, and Luis Diaz, Image Entertainment, 2007.

[25] Jiménez, Máximo Rafael. La gran aventura de la bachata urbana. Santo Domingo: Funglode, Fundación Global Democracia y Desarrollo, 2018, 39.