Narrative: 2000s: Bachata Overtakes the World

"... urban bachata is characterized by the blending of English, Spanish, hip-hop, R&B, and the traditional Dominican rhythm..."

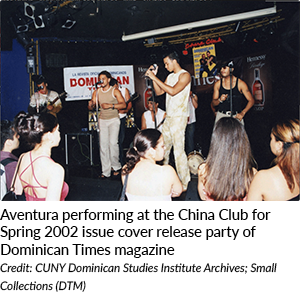

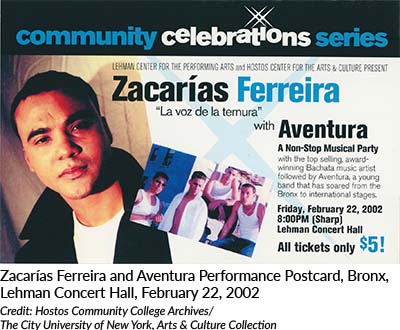

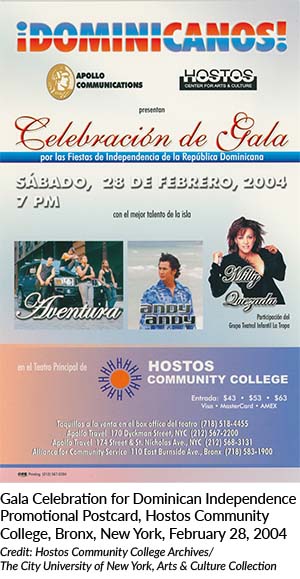

The first decade of the new millennium witnessed the galvanization of urban bachata. A fusion genre created by Dominican teenagers experimenting with popular language and music in the Bronx, urban bachata is characterized by the blending of English, Spanish, hip-hop, R&B, and the traditional Dominican rhythm bachata. Urban bachata emerged as a distinct music style in 2002 with the release of the album We Broke the Rules by Aventura.[1] The project’s leading track, “Obsesión” (click here to listen) which Rolling Stone describes as a song about “a man’s maddening desire to possess a woman… to the point that he’s lost control of himself,” was a breakout hit at the international level.[2] It was especially well-received abroad, reaching number one in various European countries including France, Austria, Germany, and Italy.[3] The key to the song’s success was its fresh urban bachata sound, cinematic lyrics, and the unique vocals of Aventura front man, Anthony “Romeo” Santos. With this formula, Aventura would go on to become urban bachata’s most revered and commercially successful act. The band’s exceptional trajectory would draw a new generation of talent to bachata, making this urban form a popular choice for young Dominican artists in the U.S., the Dominican Republic, and beyond.[4]

The first decade of the new millennium witnessed the galvanization of urban bachata. A fusion genre created by Dominican teenagers experimenting with popular language and music in the Bronx, urban bachata is characterized by the blending of English, Spanish, hip-hop, R&B, and the traditional Dominican rhythm bachata. Urban bachata emerged as a distinct music style in 2002 with the release of the album We Broke the Rules by Aventura.[1] The project’s leading track, “Obsesión” (click here to listen) which Rolling Stone describes as a song about “a man’s maddening desire to possess a woman… to the point that he’s lost control of himself,” was a breakout hit at the international level.[2] It was especially well-received abroad, reaching number one in various European countries including France, Austria, Germany, and Italy.[3] The key to the song’s success was its fresh urban bachata sound, cinematic lyrics, and the unique vocals of Aventura front man, Anthony “Romeo” Santos. With this formula, Aventura would go on to become urban bachata’s most revered and commercially successful act. The band’s exceptional trajectory would draw a new generation of talent to bachata, making this urban form a popular choice for young Dominican artists in the U.S., the Dominican Republic, and beyond.[4]

"... the Bronx, the creative headquarters of the genre..."

The majority of urban bachata groups to emerge during this decade would do so by way of the Bronx, “the creative headquarters” of the genre.[5] In a conversation with Julie Sellers, three time Latin Grammy nominated urban bachata producer sP Polanco, attributed the development of urban bachata in the Bronx to the ethnic diversity of New York City’s northernmost borough. Unlike Upper Manhattan’s historically Dominican neighborhood, he explained, the Bronx did not have the security of ethnic homogeneity, which demanded that Dominican migrants and their second-generation children determine their own emergent identities. That is, they would have to actively decide whether they would turn towards their Dominican cultural heritage or away from it. According to Polanco:

The majority of urban bachata groups to emerge during this decade would do so by way of the Bronx, “the creative headquarters” of the genre.[5] In a conversation with Julie Sellers, three time Latin Grammy nominated urban bachata producer sP Polanco, attributed the development of urban bachata in the Bronx to the ethnic diversity of New York City’s northernmost borough. Unlike Upper Manhattan’s historically Dominican neighborhood, he explained, the Bronx did not have the security of ethnic homogeneity, which demanded that Dominican migrants and their second-generation children determine their own emergent identities. That is, they would have to actively decide whether they would turn towards their Dominican cultural heritage or away from it. According to Polanco:

“That first wave of migrants [to Washington Heights] created their own community there to feel like the Dominican Republic. They wanted to feel like they were home. So the music, the bachata never evolved in Washington Heights because of that. It was still a very Dominican mentality. But when Dominicans started going to the Bronx where we didn’t have that close-knit community of Dominicans, we had to find ourselves in communities of other cultures, predominantly the Black culture and the Puerto Rican culture… I think that’s why this movement comes from the Bronx: because the Bronx wasn’t as Dominican as Washington Heights. So, it allowed us to explore our boundaries a little more….”

The turn of Bronx Dominicans towards bachata reflects a desire to maintain their connection with their ancestral homeland, the Dominican Republic, while developing specifically New York –based connections. In particular, the emergence of urban bachata reveals their interest in contributing to the Dominican Republic’s cultural soundscape. While urban bachata, at its core, is Dominican in that it maintains the base rhythm and signature sentimental themes of traditional Dominican bachata, with its incorporation of English, hip-hop, and R&B it is also very clearly grounded in New York. According to Deborah Pacini Hernandez, this fusion genre would allow second generation Dominicans to “simultaneously express their identities as urban New Yorkers and as the children of Dominican immigrants.”[6] Urban bachata became a cultural phenomenon in the U.S. and abroad because it filled a cultural and generational gap. For young Latinos living in the U.S., it served as a more relevant and relatable commentary on everyday life than did traditional bachata. For young people living in the Dominican Republic, urban bachata would serve a similar purpose and additionally would help them to know Dominicans living in the U.S.

The turn of Bronx Dominicans towards bachata reflects a desire to maintain their connection with their ancestral homeland, the Dominican Republic, while developing specifically New York –based connections. In particular, the emergence of urban bachata reveals their interest in contributing to the Dominican Republic’s cultural soundscape. While urban bachata, at its core, is Dominican in that it maintains the base rhythm and signature sentimental themes of traditional Dominican bachata, with its incorporation of English, hip-hop, and R&B it is also very clearly grounded in New York. According to Deborah Pacini Hernandez, this fusion genre would allow second generation Dominicans to “simultaneously express their identities as urban New Yorkers and as the children of Dominican immigrants.”[6] Urban bachata became a cultural phenomenon in the U.S. and abroad because it filled a cultural and generational gap. For young Latinos living in the U.S., it served as a more relevant and relatable commentary on everyday life than did traditional bachata. For young people living in the Dominican Republic, urban bachata would serve a similar purpose and additionally would help them to know Dominicans living in the U.S.

"For young Latinos living in the U.S., it served as a more relevant and relatable commentary on everyday life than did traditional bachata..."

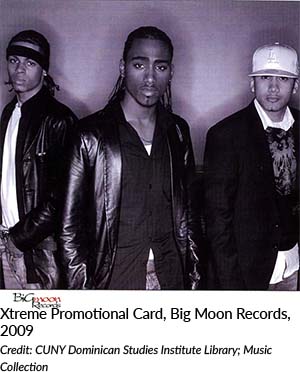

Among the most prominent urban bachata acts to emerge during this decade was the Bronx boy band Xtreme. Created by former Aventura manager, Dre “2 Strong” Hidalgo, this group would make its debut in 2003 with the release of the album We Got Next.[7] Originally a trio, Xtreme’s line-up for this project included Danny Alfredo Mejia, Steven Tejada, and Elvis Rosario. With Rosario’s departure from the group shortly after the album was recorded, however, the band would establish itself as a duo comprised of Mejia and Tejada, who were better known as Danny D. and Steve Styles.[8] As the name of the project We Got Next suggests, Xtreme was designed to become the next Aventura, which had become a household name in the urban bachata movement. In pursuit of this goal, Xtreme drew inspiration from Aventura’s work, incorporating some components of the band’s signature style, including the use of English-language New York City slang and rhythmic elements borrowed from R&B.[9] Aventura’s influence on Xtreme, however, is perhaps most evident in the core element of the duo’s music: Danny D. and Steve Styles’ voices.

Among the most prominent urban bachata acts to emerge during this decade was the Bronx boy band Xtreme. Created by former Aventura manager, Dre “2 Strong” Hidalgo, this group would make its debut in 2003 with the release of the album We Got Next.[7] Originally a trio, Xtreme’s line-up for this project included Danny Alfredo Mejia, Steven Tejada, and Elvis Rosario. With Rosario’s departure from the group shortly after the album was recorded, however, the band would establish itself as a duo comprised of Mejia and Tejada, who were better known as Danny D. and Steve Styles.[8] As the name of the project We Got Next suggests, Xtreme was designed to become the next Aventura, which had become a household name in the urban bachata movement. In pursuit of this goal, Xtreme drew inspiration from Aventura’s work, incorporating some components of the band’s signature style, including the use of English-language New York City slang and rhythmic elements borrowed from R&B.[9] Aventura’s influence on Xtreme, however, is perhaps most evident in the core element of the duo’s music: Danny D. and Steve Styles’ voices.

"... incorporating some components of the band’s signature style, including the use of English-language New York City slang..."

Apart from language and genre fusion, urban bachata of the 2000s was characterized by the ubiquity of la voceita, or the sweet high singing voice.[10] Made popular by Romeo Santos, whose high and uniquely tender voice played a primary role in Aventura’s domination of urban bachata, this tone was also common among the other acts that rose to prominence during this decade. The rise of this timbre likely stemmed from its effectiveness in intensifying the delivery of bachata’s sentimental themes. Particularly when employed in Father of Bachata Luis Segura’s classic “añoñaíto.” This tone, a whining and pleading singing style, has the ability to makes songs more tender and emotive.

Three years after the group’s debut, Xtreme would release a sophomore album prophetically titled Haciendo Historia. A significant departure from the group’s previous project, which in terms of directional clarity and production quality, more closely resembled a demo than studio album, this work established the group as a competitive participant in urban bachata. Selling over 100,000 copies within less than a year of its release, the album would achieve platinum certification.[11] This accomplishment was in large part due to the success of the project’s leading single, “Shorty, shorty”, which reached the top of the Billboard Latin Tropical Airplay chart. Reflecting the duo’s growth and potential, these achievements would earn Xtreme “Best New Group” at the 2006 Premio Lo Nuestro Awards, and a nomination for “Tropical Album of the Year” (for the platinum version of Haciendo Historia) at the 2007 Billboard Awards.[12] Xtreme would follow up this album with the release of its third and final production Chapter Dos in 2008. The band achieved moderate success with this production, the development of which was documented in the MUN2 reality TV series “Chapter Dos: On the Verge”.[13]

Another notable urban bachata act to debut during this decade was the duo Carlos & Alejandra. This duo, Bronx-born singer-songwriter Carlos Vargas and Boston-born singer Bianca Alejandra Felix (who was of both Dominican and Puerto Rican descent), most closely resemble the iconic Dominican bachata duo Monchy y Alexandra, in name and composition. Carlos & Alejandra differ from the pair, however, with their high voices and urban bachata style. The band made its debut with the album La Introducción, released on Machete Records in 2009. This project achieved great commercial success, peaking at number four on Billboard’s Tropical Albums charts.[14] The duo’s breakout single was “Cuanto Duele,” which reached number six on the Tropical Airway Chart.[15] The following year, these achievements would win the duo “Soloist or Group Revelation of the Year” at Premios lo Nuestro.”[16]

Likely, the potential of these projects were overshadowed by the release of Aventura’s highly anticipated fifth studio album The Last that same year. As the band’s first new project since its release of the 2005 album God’s Project, which reached number one on the Tropical Albums chart, The Last was highly anticipated.[17] Its ominous title, which indicated the impending breakup of Aventura also increased interest in the production. Fans or not, people interested in learning the origins of this decision to break up, would flock to the album in the hopes that it would offer some clarity on the matter. This production was a massive success, reaching number one on both the Hot Latin Albums and Tropical Albums charts. Five songs from the album entered the top five of the Hot 100 chart, with “Por un Segundo” and “Dile Al Amor,” topping the list.[18]

In the next decade, Aventura front man Romeo Santos would return to the international stage as a soloist, expanding the reach of bachata further through his own unique innovations. He was joined in the global arena by superstars such as Cardi B and Prince Royce, whose talents, like his own, transcended the boundaries of national origin, language, and style. Mostly U.S.-born or raised, these artists have taken the history of Dominican music to another level, by immersing their music fully into mainstream society.

Their story, however, is still another history of Dominican music in the making...

[1] “Aventura Biography.” Allmusic, 2020, https://www.allmusic.com/artist/aventura-mn0000054982/biography. Accessed 28 January 2020.

[2] Exposito, Suzy, Andrew Casillas, Isabel Raygoza, John Ochoa, and Marjua Estevez. “50 Greatest Latin Pop Songs.” Rolling Stone, 9 July 2018, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-latin-lists/50-greatest-latin-pop-songs-695776/aventura-obsesion-2002-2-695923. Accessed 28 January 2020.

[3] “Aventura.” Grammy Connect, 2020. https://www.grammyconnect.com/people/aventura-band. Accessed 24 January 2020.

[4] In 2018, Hajime Waki, a Honduran singer of Dominican and Japanese descent released a bachata song in Japanese and English. He also sang with Romeo Santos at a concert in Honduras. See "Cantante hondureño Hajime Waki lanza bachata escrita en japonés.” El Herald, 17 September 2018, https://www.elheraldo.hn/minisitios/hondurenosenelmundo/1216977-471/cantante-hondure%C3%B1o-hajime-waki-lanza-bachata-escrita-en-japon%C3%A9s. Accessed 28 January 2020.

[5] Molina Tamacas, Carmen. “Nueva York en el centro creativo de la bachata.” El Diario, 12 August 2018, https://eldiariony.com/2018/08/12/nueva-york-en-el-centro-creativo-de-la-bachata. Accessed 26 January 2020.

[6] Pacini Hernandez, Deborah. “Urban Bachata and Dominican Racial Identity in New York.” Cahiers D'Études Africaines, vol. 54, no. 216, 2014, 1027-1054.

[7] “We Brought You Urban Bachata’s Biggest Stars.” 2 Strong Music, 2016, http://2strongmusic.com/about. Accessed 28 January 2020.

[8] “Biografía de Xtreme.” Buena Música, 2020, https://www.buenamusica.com/xtreme/biografia. Accessed 22 January 2020.

[9] “Biografía de Xtreme.”

[10] Sellers, Julie. “Felix Nuñez.” The Modern Bachateros: 27 Interviews. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2017, 57-69.

[11] “Gold & Platinum,” RIAA, 2020, https://www.riaa.com/gold-platinum/?tab_active=default-award&se=xtreme#search_section. Accessed 28 January, 2020.

[12] “Xtreme: About.” Spotify, 2020, https://open.spotify.com/artist/47bVt95bvBMpmJFWoyhH0C. Accessed 28 January, 2020.

[13] Cobo, Leila. “Xtreme Starring in Bilingual Reality Show.” Billboard, 3 May 2009, https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/268740/xtreme-starring-in-bilingual-reality-show. Accessed 28 January 2020.

[14] “Chart History Carlos y Alejandra: Tropical Albums.” Billboard, 2020, https://www.billboard.com/music/carlos-y-alejandra/chart-history/LTS. Accessed 27 January 2020.

[15] “Chart History Carlos y Alejandra: Tropical Airplay.” Billboard, 2020, https://www.billboard.com/music/carlos-y-alejandra/chart-history/LSA/song/605410. Accessed 27 January 2020.

[16] “Carlos y Alejandra: About.” Spotify, 2020, https://open.spotify.com/artist/198g5ZZS90C4PnJ7E1dVjA?si=P6Aw4fwpQn-THUd3YEHf6A. Accessed 27 January 2020.

[17] “Chart History Aventura: Tropical Albums.” Billboard, 2020, https://www.billboard.com/music/aventura/chart-history/LTS/song/478410. Accessed 27 January 2020.

[18] “Chart History Aventura: Hot 100.” Billboard, 2020, https://www.billboard.com/music/aventura/chart-history/latin-songs. Accessed 27 January 2020.