Narrative: 1970s: Merengue Begins to Create its Own Space

In the late 1960s, the advent of salsa and boogaloo fever created a challenging musical environment for Dominican artists in the United States. While the popularity of boogaloo was short-lived, experiencing a national boom around 1966[1] and declining shortly thereafter, salsa was converted into an international phenomenon that would dominate the Latin music industry into the next two decades. During this time, merengue was pushing its way in and had the potential to match or even surpass salsa in popularity. Merengue shares some of the core qualities that made salsa into a cultural sensation as a contagious and highly danceable rhythm. Yet, compared to salsa, merengue required less movement of the feet and the arms, making merengue much easier to dance to for a novice dancer of Latin rhythm or others who were unfamiliar with merengue. However, merengue did not count on the same support as salsa from the New York City Latin recording industry. Those who dominated the music industry did not see Dominican music as a lucrative market.[2] Despite this lack of confidence, which limited merengue artists’ access to important resources including industry connections, financial backing, promotion, and distribution support, merengue began to create a space of its own, backed by a desire to preserve a cultural legacy. The decade would witness the rise of merengue acts with increased audience sizes and more live presentations with seasoned merengue artists from the Dominican Republic.

"Championed by Dominican promoters and audiences in New York City, merengue began to lay strong roots in Dominican spaces, creating a memory that would increasingly penetrate the Latin spaces of the larger society..."

Championed by Dominican promoters and audiences in New York City, merengue began to lay strong roots in Dominican spaces, creating a memory that would increasingly penetrate the Latin spaces of the larger society. The formula was simple: the larger the audience, the larger the orbit of merengue. At the time, the goal for merengueros lovers was to reach salsa’s stardom position, both at the national and international levels.

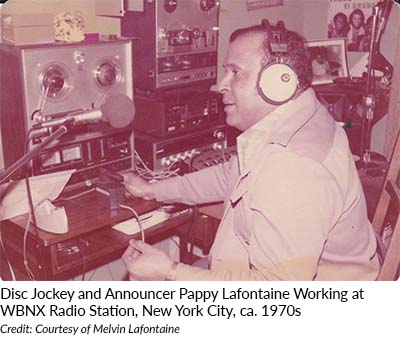

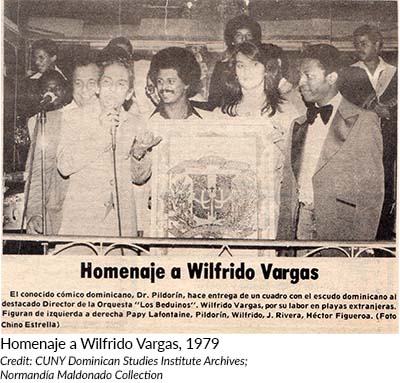

Among the chief promoters of merengue was Dominican radio jockey José “Pappy” Lafontaine. Known for his distinct hoarse voice and humor, Pappy enjoyed a rich career in broadcasting which began in his native Hato Mayor de Rey and extended to Santo Domingo and New York City.[3] In 1969, Lafontaine arrived in The Big Apple with the intention of breaking into U.S. Spanish-language radio, which he ultimately achieved at iconic stations Radio X and 97.9, better known today as La X 96.3 and La Mega 97.9. Lafontaine would begin his campaign to raise the visibility of merengue and Dominican musicians more broadly at La X, where he became privy to the structural barriers facing merengue at the time. As a way of undermining these barriers on the radio, Lafontaine cleverly began substituting merengue recordings for the songs set to air on Radio X, without making waves.[4] Soon, on February 27, 1970, “Pappy” revved up his efforts to promote merengue by debuting the first three-hour radio program exclusively dedicated to the Dominican rhythm. The following year, the broadcaster established his own full day radio program, “Sábado Dominicano,” in which merengue reigned, enjoying a privileged center stage. The show was broadcast on Saturdays from 7:30am to 9:30pm and lasted for a few years.[5]

Among the chief promoters of merengue was Dominican radio jockey José “Pappy” Lafontaine. Known for his distinct hoarse voice and humor, Pappy enjoyed a rich career in broadcasting which began in his native Hato Mayor de Rey and extended to Santo Domingo and New York City.[3] In 1969, Lafontaine arrived in The Big Apple with the intention of breaking into U.S. Spanish-language radio, which he ultimately achieved at iconic stations Radio X and 97.9, better known today as La X 96.3 and La Mega 97.9. Lafontaine would begin his campaign to raise the visibility of merengue and Dominican musicians more broadly at La X, where he became privy to the structural barriers facing merengue at the time. As a way of undermining these barriers on the radio, Lafontaine cleverly began substituting merengue recordings for the songs set to air on Radio X, without making waves.[4] Soon, on February 27, 1970, “Pappy” revved up his efforts to promote merengue by debuting the first three-hour radio program exclusively dedicated to the Dominican rhythm. The following year, the broadcaster established his own full day radio program, “Sábado Dominicano,” in which merengue reigned, enjoying a privileged center stage. The show was broadcast on Saturdays from 7:30am to 9:30pm and lasted for a few years.[5]

Given merengue’s tenuous position in New York City during the 1970s, few of the genre’s preeminent stars came from musicians already settled in the U.S. In fact, merengue would build a following with merengueros who already had name recognition in the Dominican Republic, and would travel to the U.S. to expand their career. One important outlier to this phenomenon was merengue legend Primitivo Santos who after a few years of working in the U.S. would reach national and even international projection. Primitivo arrived in Washington D.C. in 1965 where he was a member of the Dominican Republic diplomatic body.[6] Shortly after, he got a job playing piano and bandeon at a local hotel. In 1967, Primitivo Santos released his first album titled Primitivo y Su Conjunto en Washington, on Montilla Records.[7] The album featured a variety of music styles including guaracha, danzón, bolero, and merengue, a typical line-up of merengue projects during this time. By including various popular genres, merengue positioned itself to reach a larger audience. This strategy would be clearly described some years later in Santos’ “Pa’ que no te quejes,” a track record from Poema, an album released in 1973. “Pa’ que no te quejes,” (click here to listen) lyrics allude to merengueros’ decisions of including a guaguancó or salsa in their repertoire to reach a larger audience.[8] In 1967, Primitivo Santos, alongside Joseíto Mateo and Alberto Beltrán, would take merengue to Madison Square Garden. In this presentation merengue would penetrate, for the first time, a mainstream social space in the U.S. and one of the most prestigious arenas in the world.[9]

In 1971, Santos moved from Washington D.C. to New York City where he would work as a band leader with some of the best Dominican musicians, among them Héctor “Bomberito” Zarzuela, Marino Solano, and Mario Rivera. It is in New York City that Primitivo Santos would establish the connections, reputation, and following that would enable him to earn various recording opportunities.[10] Some of his top hits included “El Manicero,” “La mulatona,” and “Vuelvo pa’gozar” .[11] By the end of the decade, Santos had acquired prominence as a merengue artist, helping to seal the genre’s strong position nationally and internationally.

The neglect that merengue faced in New York City by the U.S. music industry during the 1970s extended to the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and other countries.[12] Latin music label Fania Records, founded in 1964 by Dominican-born musician Johnny Pacheco and U.S.-born Italian lawyer Gerald “Jerry” Masucci, also contributed to the pervasive neglect of merengue music during the 1970s. Fania Records was the preeminent producer and distributor of Latin music through the end of the 1970s. According to iconic Dominican disc jockey Willy Rodríguez, Fania Records joined the disdain blocking merengue because at the time “…Fania was interested in maintaining an image in the market that portrayed salsa as the representative of Latin rhythm. They had to maintain that position; merengue couldn't be Latin.” [13]

The neglect that merengue faced in New York City by the U.S. music industry during the 1970s extended to the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and other countries.[12] Latin music label Fania Records, founded in 1964 by Dominican-born musician Johnny Pacheco and U.S.-born Italian lawyer Gerald “Jerry” Masucci, also contributed to the pervasive neglect of merengue music during the 1970s. Fania Records was the preeminent producer and distributor of Latin music through the end of the 1970s. According to iconic Dominican disc jockey Willy Rodríguez, Fania Records joined the disdain blocking merengue because at the time “…Fania was interested in maintaining an image in the market that portrayed salsa as the representative of Latin rhythm. They had to maintain that position; merengue couldn't be Latin.” [13]

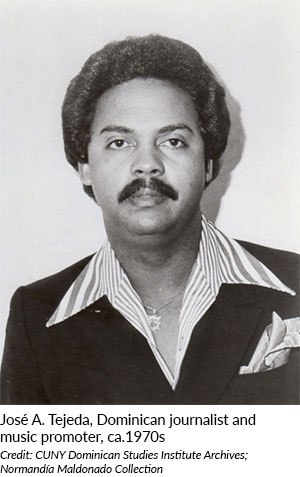

While Fania Records might have been complicit in neglecting merengue, Pacheco’s friendship with José A. Tejeda would prove fundamental for the development of merengue. Shortly after arriving in the Big Apple in 1970, Tejeda began to work as a promoter of musical shows sponsored by Fania. Tejeda supported eight events for Fania Records, an experience that propelled his career as a promotor in its own right.[14] He would become known for bringing Dominican artists, among other popular Latino acts, to legendary New York City music venues such as Madison Square Garden, Radio City Music Hall, Carnegie Hall, and Lincoln Center. Tejeda learned how to penetrate these mainstream spaces when he was promoting Fania labeled shows.[15]

In 1979, Tejeda began organizing his legendary Festival del Merengue, an annual celebration in New York City that promoted merengue’s most promising performers.[16] Some of the most popular artists to perform at Tejeda’s festivals were Johnny Ventura and Wilfrido Vargas, who appeared multiple times over the next two decades.[17] Interestingly, as merengue was rising up, salsa was experiencing some decline, as Fania Records lost its stronghold in the Latin music industry. Yet, Tejeda and Pacheco’s friendship remained strong. Throughout the years, the pair would frequently collaborate on events to promote their respective genres and even to honor each other. On May 29, 1977, Tejeda organized a tribute concert in celebration of Pacheco at the New York State Armory. Some of the most popular Dominican artists of the period appeared at this event, including Primitivo Santos and his orchestra, Johnny Ventura y sus Caballos, and Los Hijos del Rey.[18]

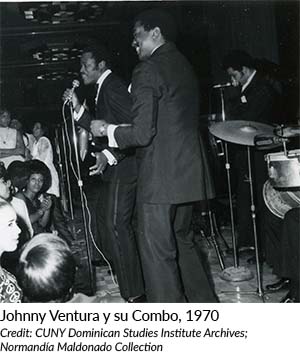

Emerging in 1964 on the Dominican music scene with his band, Johnny Ventura y Su Combo-Show, Ventura was the first merengue act to reach international projection following the assassination of Dominican dictator Rafael L. Trujillo.[19] According to “King of Merengue” Joseito Mateo, timing was central to Ventura’s success. Ventura also revolutionized merengue by introducing a number of unique innovations that made the genre livelier and more youth-oriented (click here to listen). Among the band’s most important contributions were the incorporation of rock and salsa elements and introduction of choreographed dance routines (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2) .[20]

Emerging in 1964 on the Dominican music scene with his band, Johnny Ventura y Su Combo-Show, Ventura was the first merengue act to reach international projection following the assassination of Dominican dictator Rafael L. Trujillo.[19] According to “King of Merengue” Joseito Mateo, timing was central to Ventura’s success. Ventura also revolutionized merengue by introducing a number of unique innovations that made the genre livelier and more youth-oriented (click here to listen). Among the band’s most important contributions were the incorporation of rock and salsa elements and introduction of choreographed dance routines (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2) .[20]

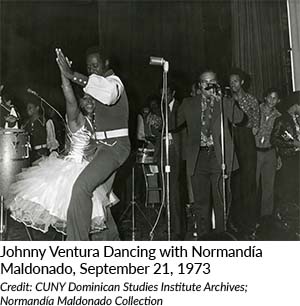

Ventura visited New York City for the first time in 1967.[21] There, as in the Dominican Republic, he would become an instant success, winning the hearts of the general public with his fresh sound and multifaceted performances. In the Big Apple, the singer would rack up a number of honors, among them record certifications, awards, and events held in his recognition. On April 25, 1970, the cultural and civic group Círculo Dominicano de Cultura held the first merengue festival in the U.S.[22] The festival at the New York Hilton Ballroom, honored Johnny Ventura y Su Combo for revolutionalizing and making merengue international. According to Luís R. Taveras, there were at least 3,500 people in attendance.[23] In 1973, Johnny Ventura performed at the Cañonazo del 1973 (click here to see flyer) at Manhattan Center alongside Normandía Maldonado y su Ballet Quisqueya, Típica 73, and Yoyito Cabrera (click here to listen). On March 1st, 1974, Johnny Ventura y Su Combo performed at The New York Latin Music Festival at Madison Square Garden in New York City. This concert featured Johnny Pacheco, Celia Cruz, Fausto Rey, Típica 73, Roberto Roena y su Apollo Sound, and Machito and Graciela.[24]

Ventura visited New York City for the first time in 1967.[21] There, as in the Dominican Republic, he would become an instant success, winning the hearts of the general public with his fresh sound and multifaceted performances. In the Big Apple, the singer would rack up a number of honors, among them record certifications, awards, and events held in his recognition. On April 25, 1970, the cultural and civic group Círculo Dominicano de Cultura held the first merengue festival in the U.S.[22] The festival at the New York Hilton Ballroom, honored Johnny Ventura y Su Combo for revolutionalizing and making merengue international. According to Luís R. Taveras, there were at least 3,500 people in attendance.[23] In 1973, Johnny Ventura performed at the Cañonazo del 1973 (click here to see flyer) at Manhattan Center alongside Normandía Maldonado y su Ballet Quisqueya, Típica 73, and Yoyito Cabrera (click here to listen). On March 1st, 1974, Johnny Ventura y Su Combo performed at The New York Latin Music Festival at Madison Square Garden in New York City. This concert featured Johnny Pacheco, Celia Cruz, Fausto Rey, Típica 73, Roberto Roena y su Apollo Sound, and Machito and Graciela.[24]

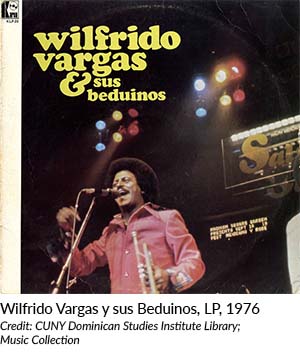

On the heels of Johnny Ventura y Su Combo-Show’s rise to prominence within the New York City Latin music scene came another trailblazing figure in the history of merengue in the Dominican Republic: Wilfrido Vargas.[25] Similar to Johnny Ventura y Su Combo-Show not just in name and composition, but also approach, Wilfrido Vargas y Sus Beduinos distinguished themselves from other merengue groups of the decade by embracing experimentation. A musical visionary and daring, Vargas pushed the boundaries of merengue by building upon Ventura’s unique innovations. The band sped up merengue’s tempo even more than Ventura had and incorporated more outside elements.[26] An original contribution attributed to Vargas and Sus Beduinos was the introduction of a shifting technique, or sudden changes in rhythm in a tune (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). The technique earned the support of younger audiences, keeping them on their feet, while it discouraged some older dancers who could not keep up with the sudden changes or were accustomed to merengue’s simpler, repetitive rhythm.

On the heels of Johnny Ventura y Su Combo-Show’s rise to prominence within the New York City Latin music scene came another trailblazing figure in the history of merengue in the Dominican Republic: Wilfrido Vargas.[25] Similar to Johnny Ventura y Su Combo-Show not just in name and composition, but also approach, Wilfrido Vargas y Sus Beduinos distinguished themselves from other merengue groups of the decade by embracing experimentation. A musical visionary and daring, Vargas pushed the boundaries of merengue by building upon Ventura’s unique innovations. The band sped up merengue’s tempo even more than Ventura had and incorporated more outside elements.[26] An original contribution attributed to Vargas and Sus Beduinos was the introduction of a shifting technique, or sudden changes in rhythm in a tune (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). The technique earned the support of younger audiences, keeping them on their feet, while it discouraged some older dancers who could not keep up with the sudden changes or were accustomed to merengue’s simpler, repetitive rhythm.

Vargas y Sus Beduinos’ first album, distributed in the Dominican Republic and the United States, was well-received in both locations. This led the group to earn a residency in 1975 at the Happy Hills Casino, owned by Puerto Rican Alvarito Ortiz, and a popular dance venue for the Dominican community. They were joined in this opportunity by compatriot and merengue peer, Félix del Rosario.[27] In 1977 Vargas and Johnny Ventura collaborated in Por El Campeonato Mundial!, an album of Discolor Records. The cover of the album featured cartoon versions of Ventura and Vargas standing in a boxing ring before a packed crowd. As the title of the album suggests, this image depicted the trailblazers’ contest for the title of best merengue artist in the world.

Vargas y Sus Beduinos’ first album, distributed in the Dominican Republic and the United States, was well-received in both locations. This led the group to earn a residency in 1975 at the Happy Hills Casino, owned by Puerto Rican Alvarito Ortiz, and a popular dance venue for the Dominican community. They were joined in this opportunity by compatriot and merengue peer, Félix del Rosario.[27] In 1977 Vargas and Johnny Ventura collaborated in Por El Campeonato Mundial!, an album of Discolor Records. The cover of the album featured cartoon versions of Ventura and Vargas standing in a boxing ring before a packed crowd. As the title of the album suggests, this image depicted the trailblazers’ contest for the title of best merengue artist in the world.

While through the next decade Vargas continued ascending in his own right, he also supported the development of various merengue-based groups including The New York Band, in New York City, and the Dominican Republic’s premiere all-women band, Las Chicas del Can. Las Chicas del Can and The New York Band would emerge in the 1980s.

The 1970s planted the seed for Dominican music to grow and develop its own authenticity in the United States. Along with music, the 1980s would witness the rise of everything Dominican. The everything- Dominican mentality would emerge from a people experiencing tremendous demographic growth and laying down permanent roots in the U.S., who wanted to preserve a cultural legacy and create their own voices to speak on their own behalf.

[1] Contreras, Félix. “Boogaloo Revival: A 1960's Fad Is Cool Again.” NPR 18 April 2011. https://www.npr.org/sections/altlatino/2011/04/19/135501205/boogaloo-revival-a-1960s-fad-is-cool-again. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[2] Austerlitz, Paul. “From Transplant to Transnational Circuit: Merengue in New York.” In Island Sounds in Global City: Caribbean Popular Music and Identity in New York, edited by Ray Allen and Lois Wilcken. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2001, 53.

[3] Socías, Augusto. “Pappy Lafontaine fue un consagrado a la promoción de nuestros artistas en Estados Unidos.” Santiago30caballeros, 13 November 2010, http://santiago30caballeros.blogspot.com/2010/11/pappy-lafontaine-fue-un-cansagrado-la.html. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[4] Rodríguez De León, Francisco. El furioso merengue del norte: Una historia de la comunidad dominicana en los Estados Unidos. New York: s.n.,1998, 94.

[5] Lafontaine, José (Pappy). Peripecias de un locutor de tercera. Santo Domingo: Editora Taller, 1995, 29.

[6] Aybar F., José Antonio. “Muere en Miami el músico Primitivo Santos.” El Nacional, 6 June 2018, https://elnacional.com.do/muere-en-miami-el-musico-primitivo-santos/. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[7] “Primitivo Su Combo – Primitivo y Su Combo en Washington.” Discogs, 2020, https://www.discogs.com/Primitivo-Y-Su-Combo-Primitivo-Y-Su-Combo-En-Washington/master/568737. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[8] “Primitivo Su Combo – Poema.” Discogs, 2020, https://www.discogs.com/Primitivo-Y-Su-Orquestra-Poema/release/5827129. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[9] Austerlitz, Paul. Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997, 125.

[10] Primitivo Santos y Su Orquesta.” Discogs, 2020, https://www.discogs.com/artist/3559283-Primitivo-Santos-y-Su-Orquesta. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[11] “El músico Primitivo Santos muere en Estados Unidos a sus 83 años.” El País, 6 June 2018, https://www.elpais.com.co/entretenimiento/celebridades/el-musico-primitivo-santos-muere-en-estados-unidos-a-sus-83-anos.html. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[12] Pacini Hernández, Deborah. Bachata: A Social History of Dominican Popular Music. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1995, 108.

[13] Pacini Hernández, Bachata, 108.

[14] Martínez, Carlos T. “Años dorados de la música en NY.” Diario Libre, 4 November 2011, https://listindiario.com/entretenimiento/2011/11/04/209655/anos-dorados-de-la-musica-en-ny. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[15] Cruz Tejada, Miguel. “Filial de ACROARTE en Nueva York declara al empresario José Tejeda padre del merengue.” Diario Libre, 6 January 2018. https://www.diariolibre.com/revista/musica/filial-de-acroarte-en-nueva-york-declara-al-empresario-jose-tejeda-padre-del-merengue-BD10023310. Accessed 31 January, 2020.

[16] Geronimo, Roberto. “Merengue.” Latin N.Y., April 1979, 52-53.

[17] Fernandez, Enrique. Billboard, 19 January, 1985, 57.

[18] Revista ¡Ahora!, vol. 16, no. 706, May 23, 1977, 77.

[19] “Johnny Ventura.” last.fm, 2007. https://www.last.fm/music/Johnny+Ventura/+wiki. Accessed 31 January, 2020

[20] Garrison, Rob. “Johnny Ventura.” In Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, edited by Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2005, 315.

[21] “Johnny Ventura.”república-dominicana-live.com, 2020. http://www.republica-dominicana-live.com/republica-dominicana/musica/merengue/jhonny-ventura.html. Accessed 31, January 2020.

[22] Taveras, R. Luís. “Ecos de un Festival.” Revista ¡Ahora!, vol. 9, no.344, June 15, 1970, 75.

[23] Taveras, “Ecos de un Festival,” 75.

[24] “Latin Scene.” Billboard, March 9, 1974, 27.

[25] Geronimo, Roberto. “Esquina Dominicana” Latin N.Y., October, 1976, 18.

[26] Austerlitz, Merengue, 93.

[27] Ysalguez Antonio, Hugo. “Faranduleando.” Revista ¡Ahora!, vol. 14, no. 617, September 8, 1975, 66.