Narrative: 1960s: The Birth of Salsa and the Rise of a U.S. Dominican Mentality

The 1960s ushered in a new era for the history of Dominican music in the U.S. During the Trujillo years, few Dominicans were granted passports to travel outside of the Dominican Republic. These travelers were people who were not known for opposing the government or were members of the privileged social class sectors in the Dominican Republic.[1] The assassination of Trujillo in 1961 and the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act stimulated the migration of working-class Dominicans to New York City, in response to internal processes in their homeland.[2] As the Dominican presence increased in New York City, a new, catchall genre called salsa, cultivated predominantly by Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians, began to dominate the city's Latin music scene in the 1960s. With the advent of salsa and the decline of mambo and cha-cha, merengue and other Dominican rhythms also took a backseat, particularly from the commercial point of view, clearing the way for the more fashionable music of the decade, salsa.

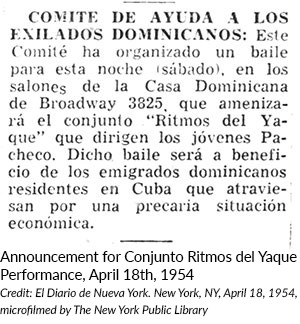

"Iconic Dominican percussionist and flautist Johnny Pacheco got his start playing in the early 1950s in a family band: Conjunto Ritmo del Yaque. Johnny Pacheco, his brothers, and their father, Rafael Azarias Pacheco, played in gatherings organized by anti-trujillistas..."

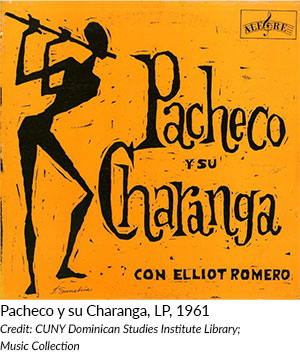

Iconic Dominican percussionist and flautist Johnny Pacheco got his start playing in the early 1950s in a family band: Conjunto Ritmo del Yaque (click here to listen to interview and recording). Johnny Pacheco, his brothers, and their father, Rafael Azarias Pacheco, played in gatherings organized by anti-trujillistas.[3] By the late 1950s, Pacheco played alongside other established Dominican artists like Dioris Valladares and Damirón and Chapuseaux. In 1960, Johnny Pacheco founded his own band and released “Pacheco y su Charanga Vol. 1,” recorded with Alegre Records in 1961. Pacheco's early recordings helped fuel the pachanga dance craze that spread in New York ballrooms until the mid-1960s (click here to listen). After the success of “Pacheco y su Charanga Vol. I,” the group headlined at the Apollo Theater in 1962. Pacheco became one of the main contributors to the birth of salsa in the 1960s, co-founding the genre’s defining label, Fania Records – the label mainly responsible for the wide dissemination of salsa - with New York impresario Jerry Masucci in 1964. That same year, Pacheco released a long-playing (LP) record titled “Mi Nuevo Tumbao… Cañonazo,” recorded with a new band, Pacheco y su Nuevo Tumbao (click here to listen). This would be Fania Records’ first recording production. Interestingly, the Fania Records label would not only sign the most prominent Puerto Rican salseros of the caliber of Willie Colon and Hector Lavoe, but it would also become synonymous with Puerto Rican identity in New York City, cultivating a movement that represented the struggles of working-class, barrio-born boricuas.

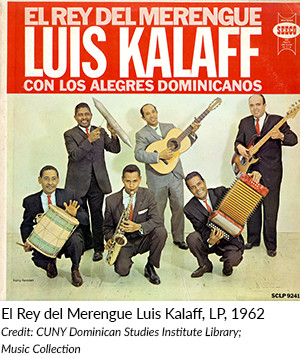

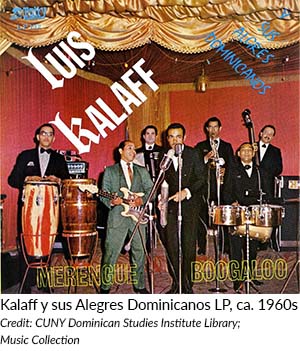

Around the same time, Dominican composer Luis Kalaff, who had been residing in New York City since 1958, recorded four merengue LPs with Seeco Records, and a few singles, from 1960 to 1963 (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). Along with singer Joseíto Mateo, Kalaff y sus Alegres Dominicanos played an accordion-based style of merengue – while also introducing the guitar – at nightclubs and theaters across Manhattan, including Teatro Puerto Rico, Club Caborrojeño, and the Palladium, before it shuttered in 1966. In time, Kalaff's diverse compositions were popularized by the likes of world-known balladist Julio Iglesias ("Empalizá") and iconic Latin music singer Celia Cruz ("Juancito Trucupey"). Kalaff also blended merengue with boogaloo, a fusion of African American R&B and soul, and mambo, which became popular among younger Latinos at the time (click here to listen). Paul Austerlitz noted that “while Kalaf music remained true to típico style, he used an expanded group consisting of accordion, tambora, güira, alto saxophone, bass, and conga drums” for larger venues.[4]

Around the same time, Dominican composer Luis Kalaff, who had been residing in New York City since 1958, recorded four merengue LPs with Seeco Records, and a few singles, from 1960 to 1963 (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). Along with singer Joseíto Mateo, Kalaff y sus Alegres Dominicanos played an accordion-based style of merengue – while also introducing the guitar – at nightclubs and theaters across Manhattan, including Teatro Puerto Rico, Club Caborrojeño, and the Palladium, before it shuttered in 1966. In time, Kalaff's diverse compositions were popularized by the likes of world-known balladist Julio Iglesias ("Empalizá") and iconic Latin music singer Celia Cruz ("Juancito Trucupey"). Kalaff also blended merengue with boogaloo, a fusion of African American R&B and soul, and mambo, which became popular among younger Latinos at the time (click here to listen). Paul Austerlitz noted that “while Kalaf music remained true to típico style, he used an expanded group consisting of accordion, tambora, güira, alto saxophone, bass, and conga drums” for larger venues.[4]

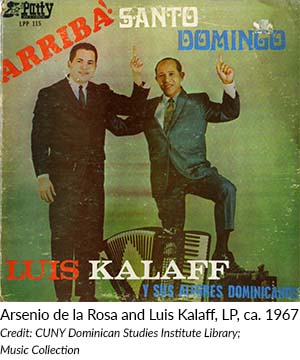

In the early 1960s, the first Dominican traditional típico accordionists, most notably Chichito Villa and Arsenio de la Rosa Caba, arrived in New York City. Rosa Caba, was part of De la Rosa Típico Dynasty, in Sydney Hutchinson’s words, alluding to a long line of traditional típico accordiniosts belonging to the same family.[5] A handful of other Dominican artists – such as trumpeter and Fania signee Bobby Quesada (click here to listen), band leader and vocalist Eddie Bastian (click here to listen), and merengue group Dominica y su Conjunto (click here to listen) – also played nightclubs and venues around the city, like the Habana San Juan and Club Caborrojeño.

In the early 1960s, the first Dominican traditional típico accordionists, most notably Chichito Villa and Arsenio de la Rosa Caba, arrived in New York City. Rosa Caba, was part of De la Rosa Típico Dynasty, in Sydney Hutchinson’s words, alluding to a long line of traditional típico accordiniosts belonging to the same family.[5] A handful of other Dominican artists – such as trumpeter and Fania signee Bobby Quesada (click here to listen), band leader and vocalist Eddie Bastian (click here to listen), and merengue group Dominica y su Conjunto (click here to listen) – also played nightclubs and venues around the city, like the Habana San Juan and Club Caborrojeño.

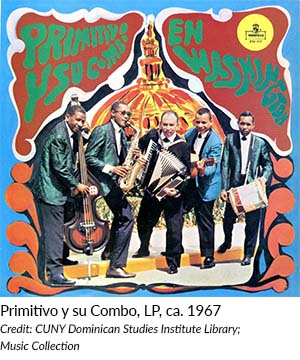

Primitivo Santos migrated to Washington, D.C. in 1965. When he moved to the U.S., his band was composed of Dominican vocalist Camboy Estévez, saxophonist Víctor Saviñon, timpanist Luciano Castro, and tamborero Gimi Pérez, and bass Alberto Martínez. They performed at hotels and clubs in Washington D.C. Santos recorded four LPs on New York-based label Montilla Records. The 1967 LP Primitivo Santos y Su Combo en Washington, particularly, a single “Union Eterna,”(click here to listen to recordings 1, 2, and 3) were his biggest hits, acquiring international recognition. On June 24th 1967, Santos debuted in New York City along with Johnny Pacheco y su Nuevo Tumbao and the orchestra of Willie Rosario in a festival organized by the Quisqueya Social Club. The event was held at the Habana San Juan Club located in Manhattan.

Primitivo Santos migrated to Washington, D.C. in 1965. When he moved to the U.S., his band was composed of Dominican vocalist Camboy Estévez, saxophonist Víctor Saviñon, timpanist Luciano Castro, and tamborero Gimi Pérez, and bass Alberto Martínez. They performed at hotels and clubs in Washington D.C. Santos recorded four LPs on New York-based label Montilla Records. The 1967 LP Primitivo Santos y Su Combo en Washington, particularly, a single “Union Eterna,”(click here to listen to recordings 1, 2, and 3) were his biggest hits, acquiring international recognition. On June 24th 1967, Santos debuted in New York City along with Johnny Pacheco y su Nuevo Tumbao and the orchestra of Willie Rosario in a festival organized by the Quisqueya Social Club. The event was held at the Habana San Juan Club located in Manhattan.

As it had in previous decades, dance remained an essential part of cultural life for Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in New York, particularly as salsa boomed into the city's uptown club scene. Dominican born dancer Novel de Omar, who migrated to the U.S. in 1957, was one of the first to direct a Dominican folkloric dance troupe in New York City, specializing in merengues and mangulinas. Novel de Omar performed at venues like the San Juan Theater, Palladium Ballroom alongside merengue bands like Ramón García y su Conjunto Típico Cibao and Luis Quintero y su Alma Cibaeña.[6]

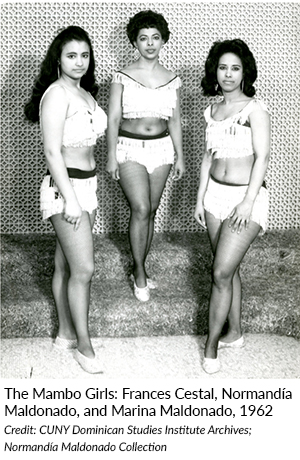

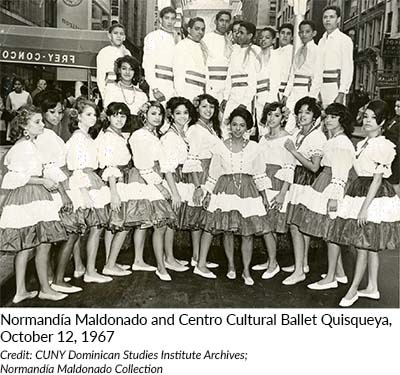

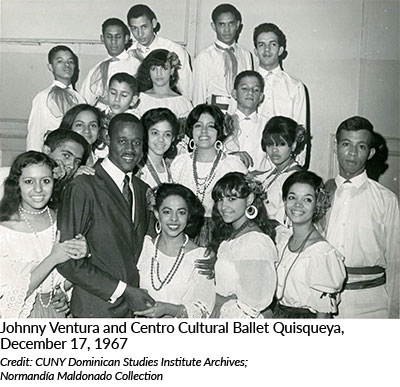

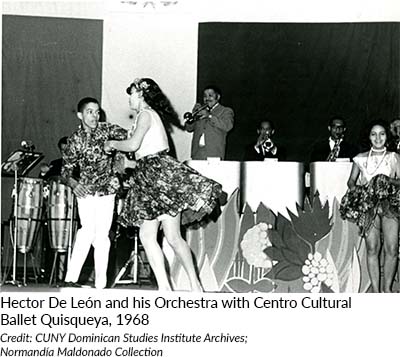

Dancer and actor Normandía Maldonado, who migrated to the U.S. in 1960, founded a dance group, the Mambo Girls, with her sister two years after arriving in the country. The group performed at Lincoln Center and on local and national television.[7] In addition to her career in the arts, Maldonado became a distinguished community leader, and along with Juan Paulino and Victor Liriano, she worked on a campaign to erect a landmark to Dominican founding father Juan Pablo Duarte on 6th Avenue and Grand Street in Lower Manhattan.[8] In 1967, the Mambo Girls adopted the name Ballet Quisqueya, later rebranding as Centro Cultural Ballet Quisqueya, Inc. It was with this group that Tito and Johnny Kenton began their early dancing careers in 1967.Their brother Luis Kenton would later join them in their professional debut as “Los Kenton” at the Teatro Puerto Rico in 1968.[9] Maldonado’s cultural initiatives helped to develop Dominican cultural life abroad, promoting education about the island's folkloric music and popular dance forms.

As they had in previous decades, Dominicans continued to play alongside Puerto Rican and Cuban artists. Hector "Cabeza" De León was a composer, arranger, and trumpeter who arrived from the Dominican Republic in New York in 1967 and joined the Tito Puente Orchestra on trumpet. In 1968, De León arranged and produced Cuban singer La Lupe's iconic albums La Lupe's Era and Queen of Latin Soul. By this time, an array of Dominican musicians had already had a long history of active participation and collaboration in the Latin music scene in New York and beyond.

As they had in previous decades, Dominicans continued to play alongside Puerto Rican and Cuban artists. Hector "Cabeza" De León was a composer, arranger, and trumpeter who arrived from the Dominican Republic in New York in 1967 and joined the Tito Puente Orchestra on trumpet. In 1968, De León arranged and produced Cuban singer La Lupe's iconic albums La Lupe's Era and Queen of Latin Soul. By this time, an array of Dominican musicians had already had a long history of active participation and collaboration in the Latin music scene in New York and beyond.

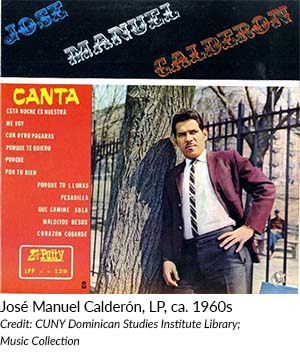

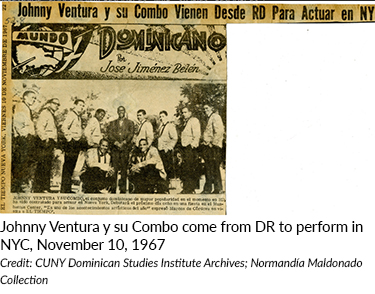

At the same time that salsa was exploding on New York City dancefloors, a musical revolution was taking place in the Dominican Republic – bachata was moving out of the countryside and into cities. In 1962, José Manuel Calderón became the first artist to record bachata, with his song "Borracho de amor." After traveling through Puerto Rico in the early 1960s, Calderón arrived in New York in 1967, performing at Las Palmeras restaurant in Queens. Calderón would go on to have a lively career performing across the U.S in cities with large Latino populations who already had a relationship with Dominican music (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). On December 8th, 1967 Dominican Johnny Ventura y su Combo debuted at the Manhattan Center and were well received by a multitude of fans.[10] Normandía Maldonado y su Ballet Quisqueya participated in a going away concert for Johnny Ventura y su Combo, on December 17th, 1967 at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan.

By the end of the 1960s, the number of Dominicans arriving into the U.S. had reached 83,552 and was growing exponentially. Many of the Dominican musicians who came as children, along with their families, were pivotal in the formation of the various Dominican communities that sprang slowly, particularly in New York City. Other communities developed in Jersey City, Miami, Washington, D.C., Providence, and Boston, as Dominicans arrived and spread throughout the U.S. In the years to come, Dominican music would transform from an immigrant and ethnic/national phenomenon into a lasting conduit of cultural expression, representing a rooted and growing Dominican people whose musical contributions would slowly penetrate U.S. culture and society as a whole.

[1] Hernández, Ramona. The Mobility of Workers under Advanced Capitalism: Dominican Migration to the United States. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002, 21.

[2] Hernández, The Mobility of Workers, 24.

[3] “Pacheco, Johnny.” Interview by David Carp. Tape recording. Manhattan, NY. April 2, 1997. The David Carp Latin Jazz Collection, Bronx County Historical Society, Bronx, New York.

[4] Austerlitz, Paul. Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1997, 141.

[5] Hutchinson, Sydney. “Merengue Típico in New York City: A History.” Camino Real, vol. 3, no. 4, 2011, 20.

[6] “Pacheco, Johnny.” Interview by David Carp. Tape recording. Manhattan, NY. April 2, 1997. The David Carp Latin Jazz Collection, Bronx County Historical Society, Bronx, New York.

[7] The CUNY Dominican Studies Institute Archives hold the Normandía Maldonado Collection, which includes videos and other materials documenting some of the tours undertaken by the Mambo Girls in the U.S. The Mambo Girls’ performance at the Lincoln Center is noted in Lisa García Bedolla’s Latino Politics (2nd ed. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity, 2014).

[8]This project came to fruition in 1978.

[9] Polanco, Fausto. Merengueros. Santo Domingo: Serigraf, 2015, 347.

[10] Revista ¡Ahora!, vol. 6, no. 214, December 18, 1967, 60.