Narrative: 1950s: Here Comes the Dominican Merengue: Mambo and Cha Cha Make Way

As mambo exploded into New York City’s mainstream in the 1950s, its rhythmic cousin cha-cha also emerged in the city’s Latin music scene. Cha-cha, as it is referred to in the U.S, in contrast to the Cuban and Latin American term chachachá, is a triple-step reimagining of Cuban danzón and mambo, adapted for the North American ballroom. As they had done with other rhythms before, Dominican musicians performed cha-cha and other trendy Cuban-derived styles of the era alongside merengue. In the 1950s, however, Dominican artists began to plant the seeds of the accordion-based merengue típico, a musical rhythm that would reach peak popularity during the 1970s in New York City as the Dominican population began to rise.[1]

"During the early 1950s, Angel Viloria y su Conjunto Típico Cibaeño became the most successful merengue group outside of the Dominican Republic..."

During the early 1950s, Angel Viloria y su Conjunto Típico Cibaeño became the most successful merengue group outside of the Dominican Republic. Despite the name, Viloria and his band played a new, hybrid form of merengue that included new instruments typically used in jazz and other music. Viloria created a fresh interpretation of the genre that blended several components: the traditional small-group structure used in merengue típico, the urban style popularized by merengue pioneers like Luis F. Alberti, the use of the bass, and the alto and tenor sax, as well as the piano accordion instead of the traditional button accordion.[2]

During the early 1950s, Angel Viloria y su Conjunto Típico Cibaeño became the most successful merengue group outside of the Dominican Republic. Despite the name, Viloria and his band played a new, hybrid form of merengue that included new instruments typically used in jazz and other music. Viloria created a fresh interpretation of the genre that blended several components: the traditional small-group structure used in merengue típico, the urban style popularized by merengue pioneers like Luis F. Alberti, the use of the bass, and the alto and tenor sax, as well as the piano accordion instead of the traditional button accordion.[2]

Viloria’s first recordings with Ansonia records in 1953, included several Dominican musicians such as Ramón E. García and Luis Quintero, who would later go on to form their own bands and earn popularity in their own right. From 1953-1954 the group recorded a number of hit singles, including "A lo Oscuro" (click here to listen) and "Consígueme Eso," (click here to listen) songs that continue to delight merengue-dancers today. Viloria's take on típico was adopted by other New York-based merengueros like Ricardo Rico, who formed his own orchestra in 1954 and performed at the Manhattan Center and Audubon Hall in the years to follow. Rico also composed and recorded several traditional merengues such as "El Hombre Marinero" (click here to listen) with Verne, RCA Victor, and Tico Records.

Dioris Valladares got his start singing merengues on the nightclub circuit, playing alongside bandleader Juanito Sanabria (click here to listen) at Club Caborrojeño on Broadway and 145th Street in 1950. In 1953, after seeing Valladares perform at Caborrojeño, Rafael Pérez[3], invited Valladares to record with Viloria and the Conjunto Típico Cibaeño. Valladares stayed with the Conjunto Típico Cibaeño until 1954, when he formed his own band, Dioris Valladares y su Conjunto Típico (click here to listen). In 1955, Dioris Valladares y su Conjunto Típico while recording with Ansonia Records also served as the house band at the Gloria Palace in Manhattan.

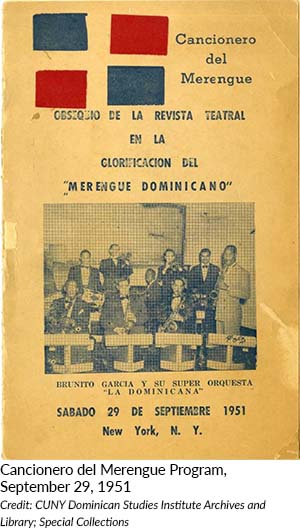

Though he is most famous for his work with the Cuban group La Sonora Matancera, Dominican singer Alberto Beltrán also helped popularize merengues like "El Negrito del Batey" (click here to listen), composed by Hector J. Díaz and Medardo Guzmán. Beltrán was known as a talented vocalist who performed a diverse repertoire of boleros, guarachas, and merengues, the majority written by Dominican composers like Kalaff. In September 1951, Beltrán traveled to New York for the Cancionero del Merengue, a celebration of the best Dominican singers, bandleaders, and composers of the era, such as Luis F. Alberti and Luis Kalaff. The event was hosted by Dominican composer and journalist Mario César de Jesús Báez and Revista Teatral, a popular celebrity magazine in New York City at the time. In 1955, he recorded Kalaff’s composition “Aunque me cueste la vida” (click here to listen) with Celia Cruz. In the mid-1950s, Beltrán moved to Cuba, becoming a Latin American star, but came back to live in New York City in the 1960s with his wife Dominican singer Carola Cuevas.

Though he is most famous for his work with the Cuban group La Sonora Matancera, Dominican singer Alberto Beltrán also helped popularize merengues like "El Negrito del Batey" (click here to listen), composed by Hector J. Díaz and Medardo Guzmán. Beltrán was known as a talented vocalist who performed a diverse repertoire of boleros, guarachas, and merengues, the majority written by Dominican composers like Kalaff. In September 1951, Beltrán traveled to New York for the Cancionero del Merengue, a celebration of the best Dominican singers, bandleaders, and composers of the era, such as Luis F. Alberti and Luis Kalaff. The event was hosted by Dominican composer and journalist Mario César de Jesús Báez and Revista Teatral, a popular celebrity magazine in New York City at the time. In 1955, he recorded Kalaff’s composition “Aunque me cueste la vida” (click here to listen) with Celia Cruz. In the mid-1950s, Beltrán moved to Cuba, becoming a Latin American star, but came back to live in New York City in the 1960s with his wife Dominican singer Carola Cuevas.

Composer and journalist Mario de Jesús used Revista Teatral as a platform to help establish merengue in the city during the early and mid-1950s. Before he began his journalistic career, de Jesús studied with Rafael Petitón Guzmán, composing songs such as "Apriétame," which was recorded by Josecito Roman y su Orquesta Quisqueya in 1949. During the same year, de Jesús also opened a business in New York City to represent musicians and singers, earning a contract from Verne, one of the most prestigious recording companies of the time.[4]

"José Ernesto "Negrito" Chapuseaux and Francisco Simó Damirón became two of the most important international ambassadors of merengue in the mid-20th century..."

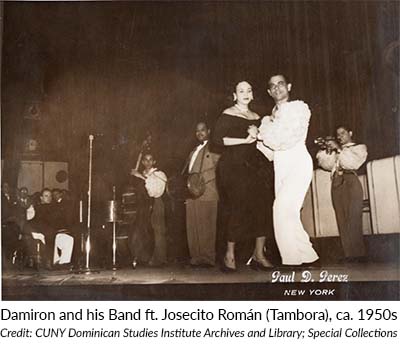

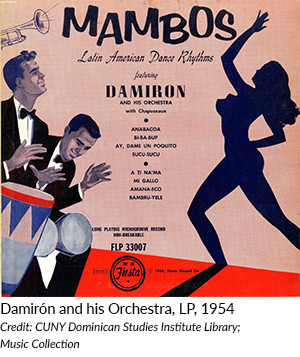

José Ernesto "Negrito" Chapuseaux and Francisco Simó Damirón became two of the most important international ambassadors of merengue in the mid-20th century. Before moving to New York City in 1949, Damirón and Chapuseaux traveled to Venezuela, Colombia, and Panamá, playing in a hybridized jazz band called Billo's Happy Boys, led by legendary Venezuela-based Dominican musician Billo Frómeta, whose band would later be renamed Billo’s Caracas Boys. When Damirón and Chapuseaux arrived in New York City, the group recorded several mambos, boleros, and merengues (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). Some songs recorded with Seeco and Atlantic garnered positive reviews in Billboard in 1950 and 1952 (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2).

José Ernesto "Negrito" Chapuseaux and Francisco Simó Damirón became two of the most important international ambassadors of merengue in the mid-20th century. Before moving to New York City in 1949, Damirón and Chapuseaux traveled to Venezuela, Colombia, and Panamá, playing in a hybridized jazz band called Billo's Happy Boys, led by legendary Venezuela-based Dominican musician Billo Frómeta, whose band would later be renamed Billo’s Caracas Boys. When Damirón and Chapuseaux arrived in New York City, the group recorded several mambos, boleros, and merengues (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). Some songs recorded with Seeco and Atlantic garnered positive reviews in Billboard in 1950 and 1952 (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2).

Like many other groups of the era, Damirón and Chapuseaux also embraced mambo rhythms in their music. A 1951 Billboard article pointed at a new moment in the Latin music scene: "There’s a decided trend toward acceptance of Latin American beats in r. & b. quarters." The article continues by adding, “Testimony of the r. & b. mambo movement is evidenced in the out-of-left-field success in New York’s Harlem of a mambo disking by Damiron, a leading Latin-American keyboard specialist, on Landia label, whose product is geared mainly for L-A buyers.”[5] In fact, by 1950, Damiron had already secured a one-year contract with Ben Maksik’s Roadside club, an important whites-only venue that had been slowly incorporating Latin artists of the caliber of Machito.

Like many other groups of the era, Damirón and Chapuseaux also embraced mambo rhythms in their music. A 1951 Billboard article pointed at a new moment in the Latin music scene: "There’s a decided trend toward acceptance of Latin American beats in r. & b. quarters." The article continues by adding, “Testimony of the r. & b. mambo movement is evidenced in the out-of-left-field success in New York’s Harlem of a mambo disking by Damiron, a leading Latin-American keyboard specialist, on Landia label, whose product is geared mainly for L-A buyers.”[5] In fact, by 1950, Damiron had already secured a one-year contract with Ben Maksik’s Roadside club, an important whites-only venue that had been slowly incorporating Latin artists of the caliber of Machito.

On February 20, 1953, Damirón and Chapuseaux played the biggest mambo concert of the year at Carnegie Hall, alongside Latin music scene veterans Tito Puente, Tito Rodríguez, and Machito. That they performed on such a prestigious stage with such distinguished and popular artists is a testament to the contributions and influences Dominicans have had on the development of major Latin music movements and the history of American music more broadly, as noted by Hal Webman’s article. By this time, Damirón and Chapuseaux were playing what Paul Austerlitz has termed as “americanized merengue,” or a type of merengue that introduced piano and maracas.[6]

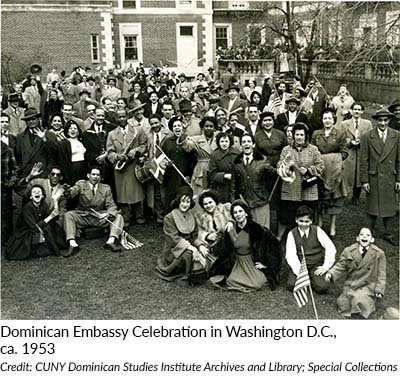

During the Trujillo dictatorship, some Dominican artists recorded songs in honor of Trujillo. In February of 1953, Ney Rivera, who was a singer, composer, and founder of the record label Riney Records, along with Rafael Rovira, composed two songs in honor of Trujillo: “Embajador Trujillo” (Ambassador Trujillo click here to listen) and “El Jefe en Nueva York” (The Chief in New York click here to listen). The writing of these songs was timely: it coincided with Trujillo’s visit to the United States to attend the general assembly meeting at the United Nations in New York City on February 24.

Malagon Sisters performed on The Ed Sullivan Show

On the cha-cha front, the Malagon Sisters were a popular vocal trio who performed in several historic New York venues, playing shows throughout the Tri-State area and in New Orleans as well throughout the 1950s. The sisters, the daughters of a Dominican man and a Haitian woman, were bona fide members of the elite circles and well-to-do families in both the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The Malagon Sisters also played in elite New York venues such as the Apollo Theater and the Copacabana. In addition, they had a standing engagement at the Chateau Madrid, located in mid-Manhattan. In 1955, they were featured as a bright new act to watch by Variety Magazine; that same year they signed to Decca Records, later recording with René Touzet and the Cha Cha Rhythm Boys (click here to listen). In the late 1950s, appearances in film and TV boosted the sisters’ career significantly. They recorded merengue songs with Ricardo Rico and his Orchestra (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). In 1956, they performed “Oyeme Mamá” (click here to listen) and "Negra Merengue" (click here to listen) in the film El vividor starring famed Mexican comedian Germán Valdés, also known as Tin-Tan. The following year, on June 9th, 1957, the Malagon Sisters performed on The Ed Sullivan Show. In 1958, the Sisters were invited to perform at the Harvest Moon Ball dance contest in Madison Square Garden.

On the cha-cha front, the Malagon Sisters were a popular vocal trio who performed in several historic New York venues, playing shows throughout the Tri-State area and in New Orleans as well throughout the 1950s. The sisters, the daughters of a Dominican man and a Haitian woman, were bona fide members of the elite circles and well-to-do families in both the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The Malagon Sisters also played in elite New York venues such as the Apollo Theater and the Copacabana. In addition, they had a standing engagement at the Chateau Madrid, located in mid-Manhattan. In 1955, they were featured as a bright new act to watch by Variety Magazine; that same year they signed to Decca Records, later recording with René Touzet and the Cha Cha Rhythm Boys (click here to listen). In the late 1950s, appearances in film and TV boosted the sisters’ career significantly. They recorded merengue songs with Ricardo Rico and his Orchestra (click here to listen to recordings 1 and 2). In 1956, they performed “Oyeme Mamá” (click here to listen) and "Negra Merengue" (click here to listen) in the film El vividor starring famed Mexican comedian Germán Valdés, also known as Tin-Tan. The following year, on June 9th, 1957, the Malagon Sisters performed on The Ed Sullivan Show. In 1958, the Sisters were invited to perform at the Harvest Moon Ball dance contest in Madison Square Garden.

In the following decade, the beginning of what would become a massive Dominican migration to the U.S. created new opportunities for aspiring and accomplished musicians.

[1] Hutchinson, Sydney. “Merengue Típico in New York City: A History,” Camino Real, vol. 3, no. 4, 2011, 119-141.

[2] Austerlitz, Paul. Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1997, 74.

[3] Founder and owner of Ansonia Records label.

[4] Torres Tejeda, Jesús. Fichero artístico dominicano. Santo Domingo: Intergrafic, 1996, 109.

[5] Webman, Hal. Billboard, February 10, 1951, 30.

[6] Austerlitz, Merengue, 74.