Narrative: 1980s: The Internationalization of Dominican Beats

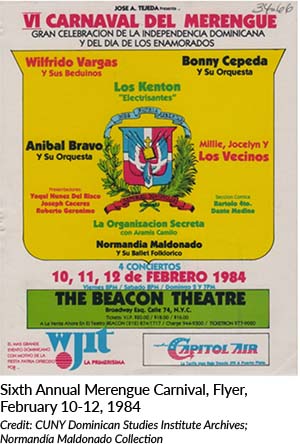

In the 1980s, after decades of vying for greater visibility and recognition, Dominican music found itself for the first time in a sustained position in the U.S. as well as on the global stage. The primary beneficiary of this heightened visibility was merengue, a music that, by all accounts, emerged reinvigorated, transformed with new vibes, and perhaps more profoundly, with new voices. The transformation included the incorporation of choreographed dance routines in performances, lyrics, rhythms, and the inclusion of women, not merely as dancers, but as first vocalists. These innovations relied on the expansion of a Dominican music industry, after Trujillo’s assassination, backed by local producers such as Bienvenido Rodriguez, the founder of Karen Records, Jose A Tejada, founder of Disco 84 records, and Raphy Pou a well-known Dominican producer. The boom of Latin music in the United States, particularly of salsa under the powerful influencer and trailblazer, Fania Records, along with fervent fans among an increasing Dominican immigrant population that longed for their culture as they set roots and established themselves in a new land, sealed the rise of merengue in the U.S., particularly in New York City.

"Quezada rose to stardom in a new era for Dominican music, one where women musicians took to center stage..."

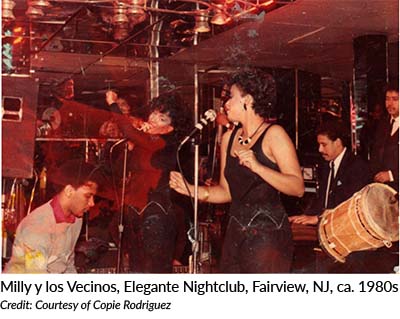

One of the most important Dominican musicians to emerge from this decade is Milagros Quezada Borbón, known artistically as Milly Quezada. Internationally recognized as the “Queen of Merengue,” Quezada rose to stardom in a new era for Dominican music, one where women musicians took to center stage. Born in Santo Domingo to Cibaeño parents in 1955, Quezada lived in the Dominican Republic until the age of 11, when her family migrated to New York City. The Quezadas settled in Washington Heights, a historically immigrant neighborhood in Upper Manhattan. Within just a few years of their arrival, Washington Heights would transform into a predominately Dominican neighborhood, known in both the United States and the Dominican Republic as the heartland of Dominicans abroad. It is the experience of migration and her longing for the Dominican Republic that inspired Quezada to become a musical artist.[1]

One of the most important Dominican musicians to emerge from this decade is Milagros Quezada Borbón, known artistically as Milly Quezada. Internationally recognized as the “Queen of Merengue,” Quezada rose to stardom in a new era for Dominican music, one where women musicians took to center stage. Born in Santo Domingo to Cibaeño parents in 1955, Quezada lived in the Dominican Republic until the age of 11, when her family migrated to New York City. The Quezadas settled in Washington Heights, a historically immigrant neighborhood in Upper Manhattan. Within just a few years of their arrival, Washington Heights would transform into a predominately Dominican neighborhood, known in both the United States and the Dominican Republic as the heartland of Dominicans abroad. It is the experience of migration and her longing for the Dominican Republic that inspired Quezada to become a musical artist.[1]

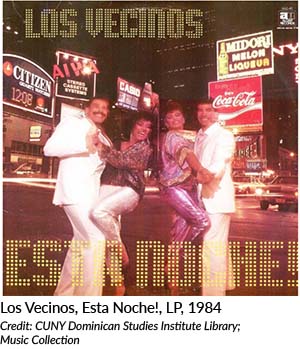

Quezada’s formal music career began in 1975 when she and her brothers, Rafael and Martín Quezada, formed the family band: Milly y Los Vecinos. In 1976 the group released their first album on Algar Records, titled Esta es Milly con los Vecinos- Tú Sabes (click here to see album). The album predominately featured merengues, the group’s primary style, though it also included some salsa and bolero songs (click here to listen). Following this debut, the band released an album every year until they disbanded in 1990, with the exception of 1978. In that year, Milly y Los Vecinos underwent some internal changes, most notably the growth of their membership with the addition of their sister, Jocelyn Quezada. Jocelyn was originally introduced to the band as a “fill in” for Milly during her first pregnancy.[2] However, as the group’s renaming to Milly, Jocelyn y Los Vecinos suggests, the younger Quezada sister slowly became a permanent member of the group. Jocelyn made her recording debut on the family band’s 1979 album, Pa’ Dominicana (click here to see album), where she lent vocals to the songs “Rocío” (click here to listen) and “Quiero" (click here to listen). [3]

"Milly, Jocelyn y Los Vecinos’ music explored universal topics such as relationships and migration..."

Milly, Jocelyn y Los Vecinos’ music explored universal topics such as relationships and migration. “Volvió Juanita” (click here to listen) from the 1984 album Esta Noche! tells the story of a Dominican woman that returns to the Dominican Republic after living in the United States for a long time. The song has become a sort of iconic symbol representing migration between the Dominican Republic and its community abroad.

Milly, Jocelyn y Los Vecinos’ music explored universal topics such as relationships and migration. “Volvió Juanita” (click here to listen) from the 1984 album Esta Noche! tells the story of a Dominican woman that returns to the Dominican Republic after living in the United States for a long time. The song has become a sort of iconic symbol representing migration between the Dominican Republic and its community abroad.

Despite the extent of the band’s travels, which took them as far as Europe, Latin America, and Asia, particularly Japan, the most important touring site for the group, apart from the United States, was their native Dominican Republic. Early on in their career, Milly, Jocelyn y Los Vecinos made touring the Dominican Republic common practice, strategically visiting around Christmas. Given that thousands of Dominicans would travel to the homeland for the holidays, returnees provided the group with an opportunity to increase the sale of hit music. Lo Mejor de Los Vecinos, released in 1987 included hits such as “La guacherna,” (click here to listen) “Tengo,” (click here to listen) and “Lo Mío es Mío,” (click here to listen) which are among Los Vecinos’ most beloved Christmas hits.

In the 1990s, Milly, Jocelyn y Los Vecinos disbanded, and Quezada reemerged as a soloist. As her title of “Queen of Merengue,” suggests, she enjoyed tremendous success in this new role. Some of her accolades includes becoming the first woman of Dominican descent to win a Latin Grammy (in the category of ‘Merengue Album of the Year’) and perform at a U.S. Presidential Inauguration Gala.[4] Quezeda’s important contributions were also recognized when she was selected in 1999 to participate in the Smithsonian Institute’s Música de las Americas en el Smithsonian: Maestros de la Música Latina programming series in Washington D.C., where she performed alongside iconic Dominican vocalists Joseito Mateo and Luis Kalaff.[5] More recently, Quezada has broadened her artistic career through her appearance in several films, including Yuniol (2007) and Juanita (2018).

With the unfortunate passing of her husband and manager, Rafael Vasquez in 1996, Quezada took a yearlong leave of absence from the music industry—her first significant break in a two decade long career.[6] In 1997, she was back on the music scene, this time with Los Vecinos, releasing the album Hasta Siempre, in homage to her husband.[7] The following year, Quezada was named “Gran Soberano,” the highest honor at the Cassandra Awards (now Soberano Awards) in the Dominican Republic.

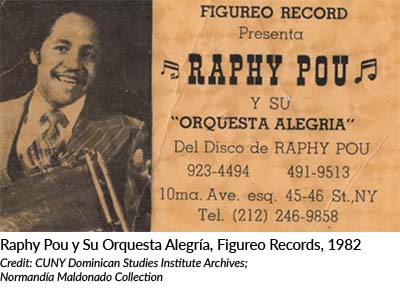

A few years after Milly y Los Vecinos debuted in 1976, an all-female merengue ensemble emerged: Las Chicas de Nueva York (click here to see photo). This band was created by Raphy Pou, a well-known producer and visionary from the Dominican Republic, known for putting together exceptional music records and acts. His most noteworthy projects include Viene Raphy Pou! (1982) (click to see album and listen to recording) by Raphy Pou’s Orquesta Alegría and Salsarengue (1983) by Joseito Mateo and La Orquesta de Rafi Pou. According to Pou, his idea to form Las Chicas de Nueva York—a uniquely all-female merengue band—emerged from “the necessities of the music scene in New York City to have an ensemble with a quality comparable to a male led orchestra.”[8]

A few years after Milly y Los Vecinos debuted in 1976, an all-female merengue ensemble emerged: Las Chicas de Nueva York (click here to see photo). This band was created by Raphy Pou, a well-known producer and visionary from the Dominican Republic, known for putting together exceptional music records and acts. His most noteworthy projects include Viene Raphy Pou! (1982) (click to see album and listen to recording) by Raphy Pou’s Orquesta Alegría and Salsarengue (1983) by Joseito Mateo and La Orquesta de Rafi Pou. According to Pou, his idea to form Las Chicas de Nueva York—a uniquely all-female merengue band—emerged from “the necessities of the music scene in New York City to have an ensemble with a quality comparable to a male led orchestra.”[8]

Likely, Raphy Pou’s decision to form Las Chicas de Nueva York was also inspired by the tremendous success of Las Chicas del Can, the first all-female merengue band, which formed in the Dominican Republic in 1976.[9] Las Chicas de Nueva York follows the similar structure of Las Chicas del Can, in terms of the group’s name and size. In addition, the lineup of both groups changed frequently—for Las Chicas de Nueva York, with each release of an album. Under Raphy Pou’s production company, the band released three albums: Merengue y Algo Mas…. (1984), Con Amor, Ritmo, y Sabor (1985) (click here to see album), and Calor Tropical (1987) (click here to see album). The group members featured on the band’s debut album are Linda Santos, Carmen Rosario, Rosa Rosario, and Carmen Rosa Santos. Carmen and Rosa Rosario would stay on for the second production and Linda Santos would make her return on the third. Vocalist Ivette Lopez was the only member who remained in the band for two consecutive productions. Other members included Genesis Sanchez and Elizabeth Ibarra, otherwise known as “Mimi.” Although merengue was the base rhythm performed by Las Chicas de Nueva York (click here to listen), salsa made its way into their recordings with songs such as “El Tapón,” (click here to listen) featured in Calor Tropical.

"Despite Las Chicas de Nueva York’s name, which firmly situates the group in the United States, the group was very proud of their Dominican heritage..."

Despite Las Chicas de Nueva York’s name, which firmly situates the group in the United States, the group was very proud of their Dominican heritage. The cover of Las Chicas de Nueva York’s first album, for instance, features a tri-colored rectangular border around an image of the original quartet posing before Manhattan skyscrapers. At each corner, the colors of this frame form the Dominican flag. The coupling of these elements, the Dominican flag and New York City high-rises, as well as the contents of the album, 8 fast-paced merengues, reflect the blending of symbols associated with the U.S. and Dominican society. The blending, would become hypervisible during this decade, as mass Dominican migration to New York City led to the transformation of the historically immigrant neighborhood of Washington Heights in Upper Manhattan into a “Little Dominican Republic.”[10]

Despite Las Chicas de Nueva York’s name, which firmly situates the group in the United States, the group was very proud of their Dominican heritage. The cover of Las Chicas de Nueva York’s first album, for instance, features a tri-colored rectangular border around an image of the original quartet posing before Manhattan skyscrapers. At each corner, the colors of this frame form the Dominican flag. The coupling of these elements, the Dominican flag and New York City high-rises, as well as the contents of the album, 8 fast-paced merengues, reflect the blending of symbols associated with the U.S. and Dominican society. The blending, would become hypervisible during this decade, as mass Dominican migration to New York City led to the transformation of the historically immigrant neighborhood of Washington Heights in Upper Manhattan into a “Little Dominican Republic.”[10]

A notable element of Las Chicas de Nueva York’s musical productions was their practice of mentioning the names of popular merengueros of the decade in their songs. By mentioning well-established figures of the scene such as Johnny Ventura and Wilfrido Vargas, Las Chicas de Nueva York increased the level of excitement among their audience as well as created a fluid conversation with their male peers, particularly those who were at their peak at that moment.

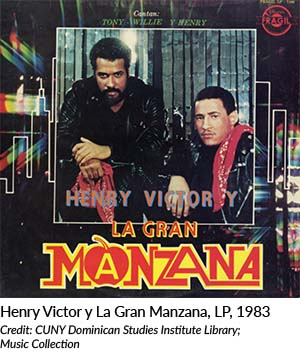

Another merengue group to leave a lasting impression on New York City’s Latin music scene was the orchestra, La Gran Manzana. Created by Victor Roque and Henry Hierro, La Gran Manzana (click here to see photo) was a joint artistic venture which came to fruition after Roque watched Wilfrido Vargas perform live in New York City—where Roque had lived since the age of 10 after migrating from Puerto Rico.[11] Despite having had no prior experience with music at that time, Roque was so moved by Vargas’ performance that he sought out Hierro, an extensively trained musician and Vargas’ former bassist, to create a band.

Apart from the group’s base location in New York City, La Gran Manzana derives its name from its members, who despite belonging to a variety of backgrounds—Dominican, Puerto Rican, Panamanian, Venezuelan—all called New York City home at the time of the orchestra’s founding.[12] Like Roque, Hierro is Dominican. He was born and raised in San Francisco de Macorís and arrived in New York City in 1979 to pursue formal musical training. According to Hierro, before leaving for the U.S., he expressed concern to Wilfrido Vargas over making the move and relocating his family: Hierro “didn’t want to leave to waste time, like many musicians who had left, and perhaps had fallen [victim to] vices or had to leave music.”[13] Despite Hierro’s fears, his decision proved fruitful. In New York City, he would enroll at the prestigious Juilliard School of Music, ultimately graduating with a degree in harmony and musical composition.[14] In the Big Apple, he would also discover his love for merengue. Before, the Hierro considered himself a rocker, but after experiencing distance from the Dominican Republic, he found himself drawn to the national music of his home country. With Roque, whose music interests by that time led him to play percussion, Hierro began to mix rock music with merengue. This openness to experimentation and fusion would become a signature element of La Gran Manzana.

Apart from the group’s base location in New York City, La Gran Manzana derives its name from its members, who despite belonging to a variety of backgrounds—Dominican, Puerto Rican, Panamanian, Venezuelan—all called New York City home at the time of the orchestra’s founding.[12] Like Roque, Hierro is Dominican. He was born and raised in San Francisco de Macorís and arrived in New York City in 1979 to pursue formal musical training. According to Hierro, before leaving for the U.S., he expressed concern to Wilfrido Vargas over making the move and relocating his family: Hierro “didn’t want to leave to waste time, like many musicians who had left, and perhaps had fallen [victim to] vices or had to leave music.”[13] Despite Hierro’s fears, his decision proved fruitful. In New York City, he would enroll at the prestigious Juilliard School of Music, ultimately graduating with a degree in harmony and musical composition.[14] In the Big Apple, he would also discover his love for merengue. Before, the Hierro considered himself a rocker, but after experiencing distance from the Dominican Republic, he found himself drawn to the national music of his home country. With Roque, whose music interests by that time led him to play percussion, Hierro began to mix rock music with merengue. This openness to experimentation and fusion would become a signature element of La Gran Manzana.

"This openness to experimentation and fusion would become a signature element of La Gran Manzana ..."

La Gran Manzana would contribute to the expansion of merengue. The group did so in two ways: (1) by utilizing advanced music technology and (2) incorporating U.S. music and styles of dress, into their recordings and live performances. Hierro has also been credited with introducing the electronic synthesizer to merengue, which he did for the first time on the group’s third album, El Poder de Nueva York, which was released in 1985.[15] This album was innovative in that it featured a merengue version of the popular U.S. hit, “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” originally recorded by Stevie Wonder in 1984 (click here to listen). Following the release of El Poder de Nueva York , Roque and Hierro went their separate ways; after which time, Roque released a series of albums under the modified title, Victor Roque y La Gran Manzana. The orchestra’s second release under this new name, Manzarengue, which was released in 1987, featured another U.S. hit, made into merengue; this time, the sampled song was “Twist and Shout,” originally recorded by The Isley Brothers in 1962.

La Gran Manzana would contribute to the expansion of merengue. The group did so in two ways: (1) by utilizing advanced music technology and (2) incorporating U.S. music and styles of dress, into their recordings and live performances. Hierro has also been credited with introducing the electronic synthesizer to merengue, which he did for the first time on the group’s third album, El Poder de Nueva York, which was released in 1985.[15] This album was innovative in that it featured a merengue version of the popular U.S. hit, “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” originally recorded by Stevie Wonder in 1984 (click here to listen). Following the release of El Poder de Nueva York , Roque and Hierro went their separate ways; after which time, Roque released a series of albums under the modified title, Victor Roque y La Gran Manzana. The orchestra’s second release under this new name, Manzarengue, which was released in 1987, featured another U.S. hit, made into merengue; this time, the sampled song was “Twist and Shout,” originally recorded by The Isley Brothers in 1962.

By 1995, La Gran Manzana would have 10 albums to its name and numerous hits. Some of the group’s most successful singles are “Dónde estás vida mía” (click here to listen) and “Por tu querer” (click here to listen). A decade after his departure, Hierro briefly returned to La Gran Manzana, a development marked in the band’s history with the release of the album, “Juntos de Nuevo” in 1996.

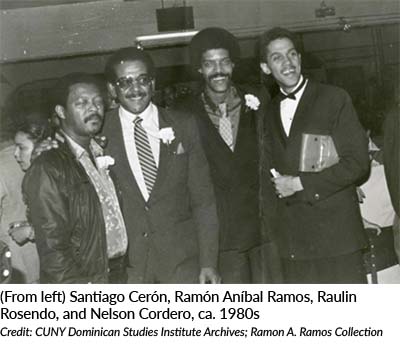

Rising concurrently in popularity with La Gran Manzana at the time of their debut was the merengue orchestra, Nelson Cordero y Su Conjunto Elegante. This group emerged on the New York City Latin music scene in 1982, with the release of its debut album, Soy. This production was developed under the guidance of Dominican arranger and musician, Héctor “Cañita” Infante, who appeared on the album’s cover alongside the group’s front man, Nelson Cordero. In 1983, Cordero released a second album, titled María Teresa, of which he was the sole creative director. While Nelson Cordero y Su Conjunto Elegante experienced limited success with its freshman and sophomore albums, the group would be catapulted into prominence with the release of its third album, Yo Soy El Varón! (click here to see album). This album, which featuring the breakout hit “Plátano Maduro” (click here to listen) would peak at number 7 on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart.[16]

Rising concurrently in popularity with La Gran Manzana at the time of their debut was the merengue orchestra, Nelson Cordero y Su Conjunto Elegante. This group emerged on the New York City Latin music scene in 1982, with the release of its debut album, Soy. This production was developed under the guidance of Dominican arranger and musician, Héctor “Cañita” Infante, who appeared on the album’s cover alongside the group’s front man, Nelson Cordero. In 1983, Cordero released a second album, titled María Teresa, of which he was the sole creative director. While Nelson Cordero y Su Conjunto Elegante experienced limited success with its freshman and sophomore albums, the group would be catapulted into prominence with the release of its third album, Yo Soy El Varón! (click here to see album). This album, which featuring the breakout hit “Plátano Maduro” (click here to listen) would peak at number 7 on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart.[16]

"The popularity of “Plátano Maduro” was rooted in its simple lyrics and contagious chorus, which featured a catchy line, “Plátano maduro no vuelve a verde,” expressing a general saying in Dominican popular wisdom..."

The popularity of “Plátano Maduro” was rooted in its simple lyrics and contagious chorus, which featured a catchy line, “Plátano maduro no vuelve a verde,” expressing a general saying in Dominican popular wisdom, or in English, “a ripe plantain doesn’t turn green again.” The song’s accompanying music video featured a well-dressed Cordero walking along Broadway in Washington Heights and greeting community members, both young and older looking people. Like Cordero, the adults and children in the video were singing along to “Plátano Maduro,” highlighting the song’s intergenerational appeal.

Following the success of this project, Cordero, now also known as “El Varón” would part ways with his orchestra in pursuit of a solo career. His first production as a solo artist, Enfoca Tu Varón, was released in 1985 on Yosi Records. Cordero continued his music career into the next decade, releasing the following albums: Sigo Siendo El Varón (1986), Savvy (1987), Mi Carrito (1989), and Looking Good! (1991).

"A creation of “El Maestro del Merengue,” Wilfrido Vargas, The New York Band represented the experience of Dominican youth growing up in New York City..."

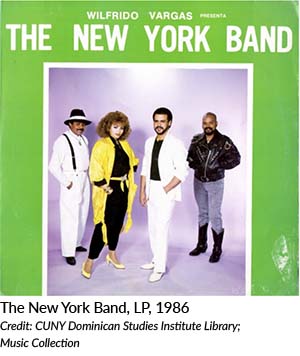

One of the most successful groups also to debut during the 1980s was The New York Band. A creation of “El Maestro del Merengue,” Wilfrido Vargas, The New York Band represented the experience of Dominican youth growing up in New York City.[17] With the help of Chery Jiménez, Vargas’ former bassist turned talent manager and producer, the group’s members were carefully selected. The most prominent among them were Irisneyda Santos and Franklyn Rivers, who primarily served as vocalists for the band.[18] A skilled musician, Rivers also served as the group’s trombonist and musical director.[19] While most of the musicians in the group were Dominican like Santos and Rivers, the band also included two musicians of Puerto Rican descent. The New York Band released its first album, Wilfrido Vargas Presenta: The New York Band, in 1986 on the legendary record label, Karen Records.

One of the most successful groups also to debut during the 1980s was The New York Band. A creation of “El Maestro del Merengue,” Wilfrido Vargas, The New York Band represented the experience of Dominican youth growing up in New York City.[17] With the help of Chery Jiménez, Vargas’ former bassist turned talent manager and producer, the group’s members were carefully selected. The most prominent among them were Irisneyda Santos and Franklyn Rivers, who primarily served as vocalists for the band.[18] A skilled musician, Rivers also served as the group’s trombonist and musical director.[19] While most of the musicians in the group were Dominican like Santos and Rivers, the band also included two musicians of Puerto Rican descent. The New York Band released its first album, Wilfrido Vargas Presenta: The New York Band, in 1986 on the legendary record label, Karen Records.

Created by Bienvenido Rodríguez, a distributor for Fania Records in the Dominican Republic, Karen Records was known for producing acts of unparalleled talent and success.[20] Some of the most recognizable acts to get their start with the label include Wilfrido Vargas, Juan Luis Guerra, Milly, Jocelyn y Los Vecinos, and Los Hermanos Rosario. Other notable talents include Las Chicas del Can, Henry Hierro, and el Ciegito de Nagua. Wilfrido Vargas has credited Rodríguez for developing his career and making him into an international artist.[21] The incredible trajectory and caliber of artists on Karen Records reveal Rodríguez’s skills and talents as a competitive producer who created a viable space for the growth of a Dominican music industry.

The New York Band’s debut album Wilfrido Vargas Presenta: The New York Band was well received in the United States and the Dominican Republic. The group’s strategy to repeat the band’s name throughout a son also played a role in creating a memory among fans who easily associated the name with the group’s rhythm. “Colé,” (click here to listen) remains one of The New York Band’s most well-known hits.[22]

Throughout the years, The New York Band incorporated new vocalists who would re-energize the band with new styles and charismas. Among the vocalists were Johnny Contreras and Alexandra Taveras (1988). Prior to joining The New York Band, Taveras attended the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where she was trained in classic music and in vocal performance.[23] The New York Band released just one album featuring Contreras and Taveras. The album, untitled, is commonly referred to as “Juicy Lucy,” the title of its leading track.[24]

Throughout the years, The New York Band incorporated new vocalists who would re-energize the band with new styles and charismas. Among the vocalists were Johnny Contreras and Alexandra Taveras (1988). Prior to joining The New York Band, Taveras attended the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where she was trained in classic music and in vocal performance.[23] The New York Band released just one album featuring Contreras and Taveras. The album, untitled, is commonly referred to as “Juicy Lucy,” the title of its leading track.[24]

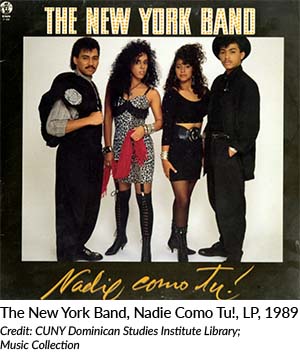

In 1989, vocalists Cherito Jiménez, son of the group’s manager, Chery Jiménez, and MioSoty Malagon, a formally trained singer and dancer from Brooklyn, joined The New York Band. Born into a Puerto Rican and Dominican household, MioSoty grew up surrounded by music, particularly merengue and salsa. As a child, her parents would often take her to music festivals in New York City. Other artists who lent their talents to the group included Tony Swing and Maggie Canales (1992), and Andy and Ariel (1995).[25] The New York Band is best known for its 2016 reunion line-up, which featured Cherito Jiménez, Franklyn Rivers, Irisneyda Santos, Alexandra Taveras, MioSoty Malagon, and Tony Swing.

With the addition of each new member, The New York Band’s style and sound experienced changes. These changes contributed to the group’s longevity by keeping audiences in suspense waiting for the latest project and innovation from the band. The New York Band ultimately became known for its choreographed dance routines and disco rhythms. “Dancing Mood,” remains one of The New York Band’s most well-known hits (click here to listen). The song appeared in their 1989 album, Nadie Como Tu!.

The New York Band would remain active into the next decade, racking up awards around the U.S. and Latin America, most notably Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Venezuela, and Chile, with its infectious sound and impressive record sales. Among the band’s greatest hits were the songs “Nadie Como Tú,” (click here to listen) “Si Tú Eres Mi Hombre,” (click here to listen) and “Dame Vida” (click here to listen).[26] In 1998, the group disbanded. Cherito and Taveras would go on to achieve success in their own right, with Cherito forming his own widely successful orchestra and Taveras going on to work as a supporting vocalist with artists of the caliber of Tito Puente and Marc Anthony.

The New York Band reunited in 2016 to perform at the Soberano Awards in the Dominican Republic, where they performed a medley of their hits. Dressed in vibrant showman costumes, the group delivered an electrifying performance, rich with fast-paced choreography and powerful vocals. The production, which brought audiences of young and old alike onto their feet, was overwhelmingly lauded as the best performance of the night. For their great career trajectory and success, the band was awarded the Merit Soberano, which honors acts that have made significant contributions to Dominican music.[27] Unfortunately, in 2019, at just 50 years old Cherito unexpectedly passed away from a heart attack.[28]

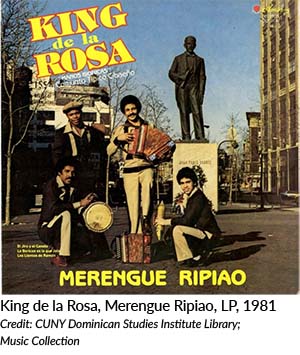

As merengue de orquesta ascended to international popularity, ultimately securing its seat on the global stage, an older and nostalgic form of merengue, merengue típico, was rising, claiming its own space in New York City. According to seminal stars in the genre, percussionist Ray “Chinito” Díaz and accordionist King de la Rosa, merengue típico grew in popularity, its demand crossing boroughs and spanning years (click here to listen). In an interview conducted by Sydney Hutchinson, Díaz revealed that to satisfy the increasing demand throughout the city, típico venues were created throughout New York City for patrons to enjoy the music:

As merengue de orquesta ascended to international popularity, ultimately securing its seat on the global stage, an older and nostalgic form of merengue, merengue típico, was rising, claiming its own space in New York City. According to seminal stars in the genre, percussionist Ray “Chinito” Díaz and accordionist King de la Rosa, merengue típico grew in popularity, its demand crossing boroughs and spanning years (click here to listen). In an interview conducted by Sydney Hutchinson, Díaz revealed that to satisfy the increasing demand throughout the city, típico venues were created throughout New York City for patrons to enjoy the music:

“Around 1984 or 1985… dozens of típico clubs appeared all over the city, the focus of activity being first in Brooklyn, then shifting to Manhattan and the Bronx in the early 1990s… Atlantic and Fulton Avenues in East New York had the greatest concentration, with clubs like Continental and Astromundo. But Sunset Park, where Ray’s family moved after leaving the Lower East Side during his elementary school years, also had many clubs.”[29]

Merengue típico clubs were established in neighborhoods with large Dominican immigrant population revealing the inexorable links between Dominicans and their homeland culture. As a folkloric genre symbolic of the Dominican Republic’s rural poor, merengue típico was reminiscent of the upbringings of many who migrated to the U.S. in the post-Trujillo period. Merengue típico, music also known as perico ripiao, uses the combination of güira, tambora, accordion, and guitar accompanied by singers not formally trained.[30] For many children born to Dominican parents in the U.S., merengue típico would become associated with cultural heritage that should be celebrated. In the next decade, these young people would heighten the genre’s visibility further by incorporating it into their music which fused the rhythm with U.S. urban influences.

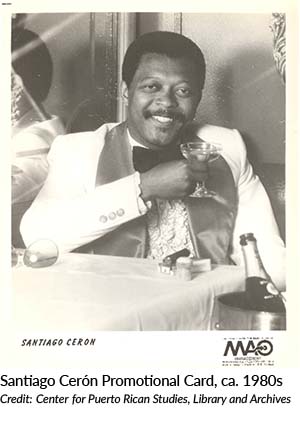

The success and rapid growth merengue experienced in the 1980s proved the genre’s ability to seriously compete with salsa, the U.S.’ reigning Latin rhythm since 1960. The appeal of merengue was rooted in its upbeat and highly infectious rhythm, which was both fresh and easy to dance to. Despite the threat merengue posed to salsa’s position “at the top,” however, the genre managed to hold its own into the next decade. One artist responsible for salsa’s endurance was singer, Santiago Cerón, who through his widely successful and popular music elevated the visibility of the music as “one of the first Dominican singers to reach international projection, especially in the Latin music spheres in New York”.[31]

Born in Santo Domingo in 1940, Cerón was an alum of la Escuela de Bellas Artes. After graduating as a lyrical tenor, Cerón was hired at the iconic radio and television station, La Voz Dominicana, where he was exclusively contracted for live performances. At age 22, the singer migrated to New York City, where he met legendary Cuban musician, Arsenio Rodríguez and was welcomed into his orchestra. Under the tutelage of Rodríguez, who was also a gifted composer and bandleader, Cerón perfected his craft. He was taught how to perform guaguancó, son montuno, and other Cuban rhythms, and made his LP recording debut.[32] Together, they released several albums, most notably the 1967 production, Arsenio Rodriguez Y Su Conjunto Vol. 2. Following his time with Rodríguez, Cerón joined the orchestra, Luis Kalaff y sus Alegres Dominicanos, where he learned to perform merengue.[33] In 1980, Cerón released his debut solo album, Tumbando Puertas, produced by Puerto Rican trumpet player Luis "Perico" Ortíz, with whom Cerón worked on other albums including, including Navegando En Sabor and Canta Si Va’ Cantar.[34] The two most popular singles from Cerón’s first album, “Lindo Yambu” (click here to listen) and “Vendedor de Agua,” (click here to listen) are songs that brought Ceron enormous fame in both the U.S. and the Dominican Republic.

Born in Santo Domingo in 1940, Cerón was an alum of la Escuela de Bellas Artes. After graduating as a lyrical tenor, Cerón was hired at the iconic radio and television station, La Voz Dominicana, where he was exclusively contracted for live performances. At age 22, the singer migrated to New York City, where he met legendary Cuban musician, Arsenio Rodríguez and was welcomed into his orchestra. Under the tutelage of Rodríguez, who was also a gifted composer and bandleader, Cerón perfected his craft. He was taught how to perform guaguancó, son montuno, and other Cuban rhythms, and made his LP recording debut.[32] Together, they released several albums, most notably the 1967 production, Arsenio Rodriguez Y Su Conjunto Vol. 2. Following his time with Rodríguez, Cerón joined the orchestra, Luis Kalaff y sus Alegres Dominicanos, where he learned to perform merengue.[33] In 1980, Cerón released his debut solo album, Tumbando Puertas, produced by Puerto Rican trumpet player Luis "Perico" Ortíz, with whom Cerón worked on other albums including, including Navegando En Sabor and Canta Si Va’ Cantar.[34] The two most popular singles from Cerón’s first album, “Lindo Yambu” (click here to listen) and “Vendedor de Agua,” (click here to listen) are songs that brought Ceron enormous fame in both the U.S. and the Dominican Republic.

Over the course of his career, Cerón released over 30 albums, half of which appeared during the 1980s.[35] He also lent his talents to other artists’ productions including Milly Quezada’s 1981 album, No te puedo tener, a salsa album containing guarachas, boleros, bomba, and bossa nova. In honor of Cerón’s contributions to salsa, in 2018 the northeast corner of Sickles Street and Sherman Avenue in Washington Heights was named, Santiago Cerón Way, making Cerón the first Dominican artist to have a street named after him.[36]

"In honor of Cerón’s contributions to salsa, in 2018 the northeast corner of Sickles Street and Sherman Avenue in Washington Heights was named, Santiago Cerón Way, making Cerón the first Dominican artist to have a street named after him..."

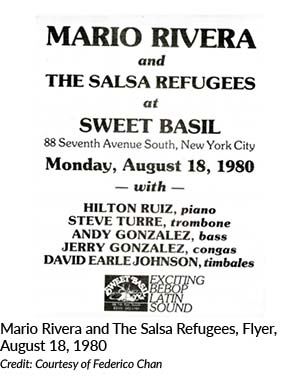

While by the 1980s, merengue and salsa had become the dominant rhythms of the New York City Latin music scene, an earlier favorite of local audiences, Latin jazz, remained in full production. One artist who contributed significantly to the development of Latin jazz, and jazz in general, was Dominican musician, composer, and arranger, Mario Rivera. Born in the Dominican Republic in 1939, Rivera was a tremendous talent who played thirteen instruments including piano, tambora, vibraphones, and trumpet. He was best known, however, for playing the saxophone and flute.

Already as a child, Rivera played the tambora drum, which is essential to merengue, around the house. Before leaving the Dominican Republic in 1961, he worked with Antonio Morel y su Orquesta, one of the country’s best merengue bands, which often performed at events attended by President Trujillo. He also played at La Voz Dominicana radio station with Orquesta Angelita, which was led by Tavito Vásquez, who is known as the best Dominican jazz musician of all time. Vásquez frequently played jazz solos with this group, and Rivera later remembered that listening to these was his “initiation into jazz.” Already during this period, Rivera experimented with merengue, adapting tambora beats to 5/4 meter by playing along with Dave Brubeck’s hit, “Take Five.”

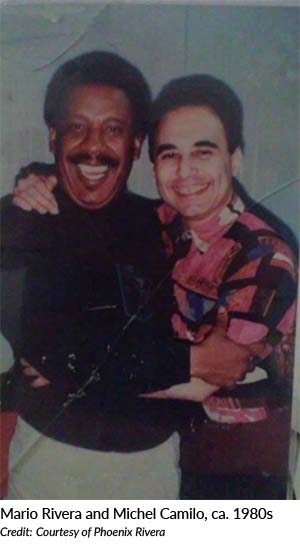

Shortly after arriving in New York City at age 22, this music virtuoso crossed paths with Puerto Rican vocalist Tito Rodríguez, with whom he would play his first gigs in the Big Apple. In the years that followed, his talents made him one of the most in demand musicians of New York City’s Latin music circuit. Over the course of his almost 50 year long career, Rivera would work with artists of the caliber of Tito Rodríguez, Machito, Típica ’73, Eddie Palmieri, and Mongo Santamaría, among others (click here to listen to recording). In 1988, he joined Dizzy Gillespie’s United Nation’s Orchestra and later, became a member of the Lincoln Center Afro-Latin Jazz Big Band, which was directed by Cuban composer and conductor, Chico O’Farrill. Although Rivera achieved success and recognition with these ensembles, he is mostly remembered for his work with Tito Puente, which spanned a duration of more than 15 years. Often featured as a soloist with Puente, Rivera appearances in the 1992 motion picture film Calle 54 and the 2001 documentary The Mambo Kings.

"When Figueroa joined the group, he wanted to play congas, but Rivera asked him to double on tambora..."

Despite being in high demand as a sideman, Rivera also formed his own band, The Salsa Refugees in 1977. While the group’s name might sound like a reference to immigration issues, it actually referred to musicians’ desire to move away from commercial salsa to develop new musical modes, and for Rivera, these modes meant a returned focus on Dominican rhythms. The Salsa Refugees played Cuban and Brazilian pieces, but its most original contribution was the use of merengue and palos. Rivera’s percussionists Julito Figueroa, Ray Chinito Díaz, and Isidro Bobadilla, all Dominicans, instigated rhythmic experiments, using unconventional combinations such as two tamboras and conga. When Figueroa joined the group, he wanted to play congas, but Rivera asked him to double on tambora. Figueroa took Rivera’s advice to heart, developing a unique style of tambora drumming as a solo improviser’s art. During his childhood, Rivera’s grandmother had taken him to ceremonies where Afro-Dominican ritual music drumming was played, as he later explained: “I used to go and listen and we stayed up all night long and they were singing all those chants, and …the palos played.” The Salsa Refugees employed palos on arrangements of Afro-centric compositions by the jazz innovator John Coltrane such as “Equinox” and “Spiritual.” With the Salsa Refugees, Rivera performed at highly renowned venues for Latin music such as Sweet Basil, Seventh Avenue, and Sounds of Brazil, usually referred to with the acronym SoBs. Over the course of his fruitful career, Rivera recorded just one solo album, El Comandante…The Merengue - Jazz, released on Groovin’ High Records in 1996 (click here to see album and listen to recording). The album seamlessly alternates between straight-ahead jazz, Afro-Cuban jazz, and merengue-jazz. Its great success earned Rivera the nickname “El Comandante.”

Despite being in high demand as a sideman, Rivera also formed his own band, The Salsa Refugees in 1977. While the group’s name might sound like a reference to immigration issues, it actually referred to musicians’ desire to move away from commercial salsa to develop new musical modes, and for Rivera, these modes meant a returned focus on Dominican rhythms. The Salsa Refugees played Cuban and Brazilian pieces, but its most original contribution was the use of merengue and palos. Rivera’s percussionists Julito Figueroa, Ray Chinito Díaz, and Isidro Bobadilla, all Dominicans, instigated rhythmic experiments, using unconventional combinations such as two tamboras and conga. When Figueroa joined the group, he wanted to play congas, but Rivera asked him to double on tambora. Figueroa took Rivera’s advice to heart, developing a unique style of tambora drumming as a solo improviser’s art. During his childhood, Rivera’s grandmother had taken him to ceremonies where Afro-Dominican ritual music drumming was played, as he later explained: “I used to go and listen and we stayed up all night long and they were singing all those chants, and …the palos played.” The Salsa Refugees employed palos on arrangements of Afro-centric compositions by the jazz innovator John Coltrane such as “Equinox” and “Spiritual.” With the Salsa Refugees, Rivera performed at highly renowned venues for Latin music such as Sweet Basil, Seventh Avenue, and Sounds of Brazil, usually referred to with the acronym SoBs. Over the course of his fruitful career, Rivera recorded just one solo album, El Comandante…The Merengue - Jazz, released on Groovin’ High Records in 1996 (click here to see album and listen to recording). The album seamlessly alternates between straight-ahead jazz, Afro-Cuban jazz, and merengue-jazz. Its great success earned Rivera the nickname “El Comandante.”

Pianist Michel Camilo (a.k.a. Michael Camilo) emerged as the single most successful Dominican jazz musician of all time. Born in Santo Domingo in 1954, he studied classical music at the Dominican National Conservatory as a youth, performing with the Dominican National Symphony Orchestra already at the age of sixteen. Camilo developed a love for jazz at a young age and, in 1979, moved to New York City to pursue this interest. There, he also continued his formal music studies at the Mannes College and Julliard School of Music. Camilo soon sky-rocketed to fame; already in 1983, he was performing with Tito Puente, and soon after that, he became a regular member of Cuban saxophonist Paquito d’Rivera’s band. Possessing virtuosic skill as a pianist, Camilo’s greatest contributions have been as a composer.

"Camilo developed a polished and highly original style blending Latin rhythms with jazz and funk in effervescently catchy tunes, which in the end became a musical style in itself, one that clearly brings in Camilo’s Dominican cultural legacy ..."

Most Latin jazz uses Cuban or Brazilian rhythms, and while experimenters such as Mario Rivera fuse merengue and palos with jazz, Camilo developed a polished and highly original style blending Latin rhythms with jazz and funk in effervescently catchy tunes, which in the end became a musical style in itself, one that clearly brings in Camilo’s Dominican cultural legacy . Several prominent musicians have affirmed Camilo’s excellence as a composer by recording their own versions of his pieces. Paquito d’Rivera, for example, used Camilo’s “Why Not!” (click here to listen) as the title tune for one of his most successful albums, and the famed Manhattan Transfer vocal group’s recording of the same piece won a Grammy Award in 1983.[37] Camilo’s compositions have also been used in several Spanish language films.[38] Camilo has received a number of awards, including Grammys, an Emmy, and several Soberanos. He also received honorary doctorate degrees from the Berklee College of Music in Boston, La Universidad Nacional Pedro Henriquez Ureña, and his alma mater, La Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo.[39]

Most Latin jazz uses Cuban or Brazilian rhythms, and while experimenters such as Mario Rivera fuse merengue and palos with jazz, Camilo developed a polished and highly original style blending Latin rhythms with jazz and funk in effervescently catchy tunes, which in the end became a musical style in itself, one that clearly brings in Camilo’s Dominican cultural legacy . Several prominent musicians have affirmed Camilo’s excellence as a composer by recording their own versions of his pieces. Paquito d’Rivera, for example, used Camilo’s “Why Not!” (click here to listen) as the title tune for one of his most successful albums, and the famed Manhattan Transfer vocal group’s recording of the same piece won a Grammy Award in 1983.[37] Camilo’s compositions have also been used in several Spanish language films.[38] Camilo has received a number of awards, including Grammys, an Emmy, and several Soberanos. He also received honorary doctorate degrees from the Berklee College of Music in Boston, La Universidad Nacional Pedro Henriquez Ureña, and his alma mater, La Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo.[39]

The spread, conservation, and preservation of Dominican music in the U.S. counted on the support of an emergent Dominican music industry, represented by José A. Tejeda . Tejada created a record label, Disco 84, and supported the careers of several performers like Héctor Lavoe, El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico, Rey Reyes, Wilfrido Vargas, Fernando Villalona, Celia Cruz, and Juan Luis Guerra. Tejada also helped Dominican artists gain access to prestigious venues in New York City such as Madison Square Garden, Radio City Music Hall, Carnegie Hall, and the Lincoln Center.

The spread, conservation, and preservation of Dominican music in the U.S. counted on the support of an emergent Dominican music industry, represented by José A. Tejeda . Tejada created a record label, Disco 84, and supported the careers of several performers like Héctor Lavoe, El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico, Rey Reyes, Wilfrido Vargas, Fernando Villalona, Celia Cruz, and Juan Luis Guerra. Tejada also helped Dominican artists gain access to prestigious venues in New York City such as Madison Square Garden, Radio City Music Hall, Carnegie Hall, and the Lincoln Center.

In the next decade, Dominican musicians in the U.S. would continue to exhibit excellence on the international stage with the emergence of distinct fusion-style genres such as merengue house and modern bachata.

[1] Hernández, Ramona and Anthony Stevens-Acevedo. “Dominican Immigrants” In Multicultural America: An Encyclopedia of the Newest Americans, edited by Ronald H. Bayor. Westport: Greenwood, 2011, 513.

[2] Pareles, Jon. “New Jersey Sisters Lead Hot Merengue Group.” The New York Times, 27 October, 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/10/27/arts/new-jersey-sisters-lead-hot-merengue-group.html. Accessed 4 October, 2019.

[3] Polanco, Fausto. Merengueros. Santo Domingo: Serigraf, 2015, 372.

[4] 1990, U.S. President George H.W. Bush.

[5] Minaya, Luis. “Música de las Américas en el Smithsonian: Maestros de la música latina.” El Pregonero, February 25, 1999, 15.

[6] “Sobre Milly.” Millyquezadaonline.com, 2019, http://millyquezadaonline.com/sobre-milly. Accessed 4 October, 2019.

[7] Boidi, Carla. “Hear Her Roar.” Miami New Times, 21 June, 2001, https://www.miaminewtimes.com/music/hear-her-roar-6351856. Accessed 4 October, 2019.

[8] Las Chicas de Nueva York. Las Chicas de Nueva York-Merengue y Algo Mas. Caiman Records, 1984.

[9] Storm Roberts, John. The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, 231.

[10] In September of 2018, Washington Heights was officially designated as Little Dominican Republic. The designation was sponsored by the then Senator, the Honorable Marisol Alcántara.

[11] “Victor Roque | BIO 23 | Una producción de Telefuturo canal 23.” YouTube, uploaded by Telefuturo 23, 22 February 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6kvB_j2B1dA&t=1686s. Accessed 13 October, 2019.

[12] “Henry Hierro, la historia de un cantante de merengue.” Listín Diario, 2 January, 2008, https://listindiario.com/entretenimiento/2008/01/02/42670/henry-hierro-la-historia-de-un-cantante-de-merengue. Accessed 13 October, 2019.

[13] “Henry Hierro, la historia de un cantante de merengue”

[14] Martínez Hernández, Rolando. El merengue: Historia y secretos. Newark and Santo Domingo: Roherma Ediciones, 2019, 211.

[15] Austerlitz, Paul. Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1997, 126.

[16] Billboard, October 13, 1984, 61.

[17] “Tania Baez Entrevista a Cherry Jimenez Padre de Cherito y Manager de The New York Band - 1988.” YouTube, uploaded by Chamakiito93, 2 December 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-InoTtuHkw. Accessed 13 October, 2019.

[18] Martínez Hernández, El merengue, 216.

[19] “Veinte años después The New York Band regresa con sus éxitos a la ciudad que le vio nacer.” Diario Libre, 25 May, 2019, https://www.diariolibre.com/revista/musica/veinte-anos-despues-the-new-york-band-regresa-con-sus-exitos-a-la-ciudad-que-le-vio-nacer-EN12860774. Accessed 16 October, 2019.

[20] Austerlitz, Merengue, 97.

[21] Vargas, Wilfrido. “Bienvenido Rodríguez: El Rey Midas Dominicano.” Diario Libre, 18 July, 2018, https://www.diariolibre.com/revista/musica/bienvenido-rodriguez-el-rey-midas-dominicano-NF10378126. Accessed 16 October, 2019.

[22] Harvey, Sean. The Rough Guide to the Dominican Republic. New York, N.Y: Rough Guides, 2009, 367.

[23] Alexandra Taveras. About. Facebook, February 14, 2009, https://www.facebook.com/pg/AlexandraSings/about/, Accessed 10 December 2019.

[24] “The New York Band.” Wilson & Alroy’s Record Reviews, http://www.warr.org/nyband.html. Accessed 10 December, 2019.

[25]“The New York Band.”

[26] “The New York Band.”

[27] @soberanoRD. “New York band recibe el premio al mérito por su gran trayectoria.” Twitter, 31 May 2016, 7:51pm, https://twitter.com/SoberanoRD/status/737838990510825473.

[28] Oyola, Michelle. “Muere Cherito de la New York Band: ¿Cómo murió el cantante?” Ahoramismo.com, 24 July 2019, https://ahoramismo.com/entretenimiento/2019/07/cherito-muerto-new-york-band-infarto/. Accessed 3 December, 2019.

[29] Hutchinson, Sydney. “Merengue Típico in New York City: A History.” Camino Real, vol. 3, no. 4, 2011, 119-141.

[30] Hutchinson, Sydney. Tigers of a Different Stripe: Performing Gender in Dominican Music. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2016, 223.

[31] “Street Co-Naming Ceremony To Honor The Musical Contributions of Santiago Cerón.” Harlem World Magazine, 15 November 2018, https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/street-co-naming-ceremony-to-honor-the-musical-contributons-of-santiago-ceron-video/. Accessed 22 October, 2019.

[32] Rendón Ángel, Sergio. “Presentación Santiago Pérez Cerón ‘El tenor lírico de la Salsa.’” Latinastereo.com, July 2009, http://old.latinastereo.com/html/genteLatina/salseroMes/SantiagoCeron/Default.shtm. Accessed 3 December, 2019.

[33] “Los Amigos.” Fania.com, 2019, https://www.fania.com/products/los-amigos?_pos=1&_sid=8cadcab47&_ss=r. Accessed 2 January 2020.

[34] “Fallece sonero Santiago Cerón.” Diario Libre, 10 May 2011, https://www.diariolibre.com/revista/fallece-sonero-santiago-cern-FCDL289936. Accessed 26 October, 2019.

[35] “Santiago Ceron.” Discogs.com, 2020, https://www.discogs.com/artist/2225768-Santiago-Ceron. Accessed 24 January 2020.

[36] “Street Co-Naming Ceremony"

[37] Austerlitz, Paul. Jazz Consciousness: Music, Race, and Humanity. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2005, 115-16.

[38] Program Biography.” michelcamilo.com, 2019, https://www.michelcamilo.com/program-biography. Accessed 11 December 2019.

[39] “Official biography.” michelcamilo.com, 2019, https://www.michelcamilo.com/official-biography. Accessed 11 December, 2019.