Narrative: 1940s: Dominican Music and the Birth of the Mambo

"It was also during this decade that Dominican composers began to forge a kind of music that resonated mostly with those who lived the migrant experience..."

In the 1940s, the rise of the mambo continued to pave the way for Dominican musicians in the U.S. It was also during this decade that Dominican composers began to forge a kind of music that resonated mostly with those who lived the migrant experience. These were nostalgic songs that alluded to some of the pain associated with migration or with missing one’s homeland. Two such songs were "Lejos de Mi Tierra" and "Mi Quisqueya (click here to listen)," musical compositions included in the compilation Songs and Dances of the Dominican Republic, a songbook that contained many of the merengues performed at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.[1] The emergent new developments made sense. The 1940s were the formative years of a music inspired by events taking place over the course of almost two decades of close contact with U.S. soil; a milieu where Dominican musicians rubbed elbows everyday with Cuban, Black, and especially Puerto Rican musicians with whom they shared the experience of exclusion and overt discrimination. The new reality would inspire and motivate Dominican musicians to start developing a new, distinct music; one that preserved the musical instruments and rhythms from the homeland but which was nevertheless autochthonous to the social space in which it emerged.

"Petitón Guzmán was one of the most influential composers in the 1940s, despite the fact that he is scarcely discussed in music historiography both in the Dominican Republic and the United States..."

Petitón Guzmán was one of the most influential composers in the 1940s, despite the fact that he is scarcely discussed in music historiography both in the Dominican Republic and the United States. While Angel Viloria is largely credited with popularizing merengue in the U.S. in the 1950s, Petitón, along with Luis Herrero and José G. Ramírez Peralta, laid the foundation long before Viloria’s arrival in the late 1940s. In 1941, Petitón recorded 8 tracks with RCA Victor, but earlier, from 1936 up to 1948, Petitón y Sus Rumberos, another group led by Petitón, held a residency at the famed Cuban Casino. Petitón played at the Stork Club alongside Johnny Rodríguez, the brother of the Puerto Rican mambo pioneer Tito Rodríguez.[2] During this time, Petitón introduced merengue to a multiethnic audience at Latin venues across the city, in a repertoire that included primarily Cuban rhythms.

Petitón Guzmán was one of the most influential composers in the 1940s, despite the fact that he is scarcely discussed in music historiography both in the Dominican Republic and the United States. While Angel Viloria is largely credited with popularizing merengue in the U.S. in the 1950s, Petitón, along with Luis Herrero and José G. Ramírez Peralta, laid the foundation long before Viloria’s arrival in the late 1940s. In 1941, Petitón recorded 8 tracks with RCA Victor, but earlier, from 1936 up to 1948, Petitón y Sus Rumberos, another group led by Petitón, held a residency at the famed Cuban Casino. Petitón played at the Stork Club alongside Johnny Rodríguez, the brother of the Puerto Rican mambo pioneer Tito Rodríguez.[2] During this time, Petitón introduced merengue to a multiethnic audience at Latin venues across the city, in a repertoire that included primarily Cuban rhythms.

During this time, merengue was disseminated largely through songbook compilations that included songs, musical arrangements, and other details about the composers. After his arrival to the U.S. in 1936, the influential folklorist Jose G. Ramírez Peralta was a major force in compiling and disseminating Dominican music, with 5 compilations to his credit, several music concerts, and radio presentations.[3]

During this time, merengue was disseminated largely through songbook compilations that included songs, musical arrangements, and other details about the composers. After his arrival to the U.S. in 1936, the influential folklorist Jose G. Ramírez Peralta was a major force in compiling and disseminating Dominican music, with 5 compilations to his credit, several music concerts, and radio presentations.[3]

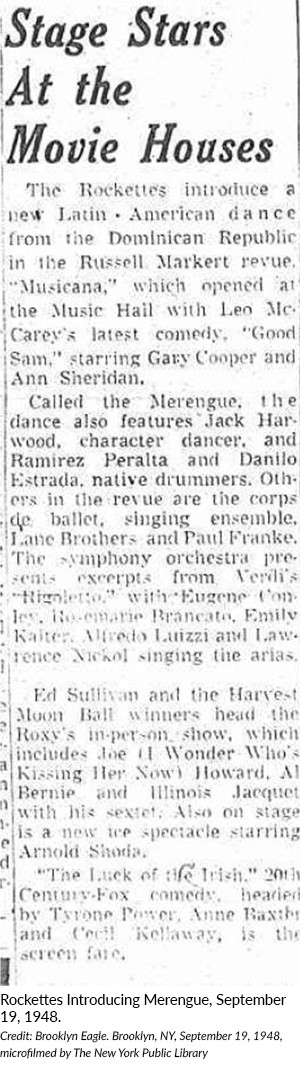

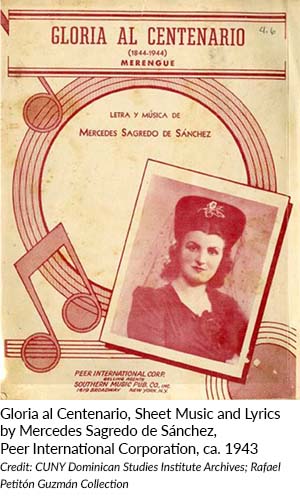

In 1941, Ramírez Peralta compiled another songbook for Alpha Music titled “Popular Airs of the Dominican Republic, Volume 1” which featured works by the most prominent composers of the time, such as Rafael Petitón Guzmán, Mercedes Sagredo de Sánchez, Rafael Ignacio, Rafael Almánzar, Julio A. Hernández, Luis F. Alberti, and Luis Herrero. Ramírez Peralta continued performing for large international audiences, for example playing at the Pan American Union Concert, sponsored by the U.S. government in Washington D.C., on December 5th of 1943. In 1944, Ramírez Peralta would publish another songbook, “National Music of the Dominican Republic,” to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Dominican independence. [4] The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper published a brief article describing a performance at the Radio City Music Hall in 1948, in which Ramírez Peralta and Danilo Estrada played the tambora with the symphony orchestra, and the Rockettes introduced a “merengue dance” to the American audience.[5]

Josecito Román y su Orquesta Quisqueya (click here to listen to recording) were among the first to promote merengue in New York City. In 1947, Roman’s band, along with 5 other Latin bands, ushered in a new Latin musical era at the Palladium Ballroom in Manhattan. Román’s merengue orchestra regularly performed during "merengue-mambo" nights at the Palladium, as well as at the Hunts Point Palace, and the Tropicana Club in the Bronx, sometimes even playing on the same bill as Noro Morales and Miguelito Valdes, notable musicians in the Latin music scene in New York City at the time.[6] The Palladium is widely recognized as the incubator of the mambo craze, a multicultural venue where African-Americans, Latinos, Jews, and Italians would line up for mambo dance contests. Though mambo and similarly trendy styles reigned supreme, these audiences were regularly exposed to Dominican rhythms as well, becoming a part of the long history of Dominican presence in Latin music in New York City.

Josecito Román y su Orquesta Quisqueya (click here to listen to recording) were among the first to promote merengue in New York City. In 1947, Roman’s band, along with 5 other Latin bands, ushered in a new Latin musical era at the Palladium Ballroom in Manhattan. Román’s merengue orchestra regularly performed during "merengue-mambo" nights at the Palladium, as well as at the Hunts Point Palace, and the Tropicana Club in the Bronx, sometimes even playing on the same bill as Noro Morales and Miguelito Valdes, notable musicians in the Latin music scene in New York City at the time.[6] The Palladium is widely recognized as the incubator of the mambo craze, a multicultural venue where African-Americans, Latinos, Jews, and Italians would line up for mambo dance contests. Though mambo and similarly trendy styles reigned supreme, these audiences were regularly exposed to Dominican rhythms as well, becoming a part of the long history of Dominican presence in Latin music in New York City.

"Men are not the only ones making waves during the 1940s..."

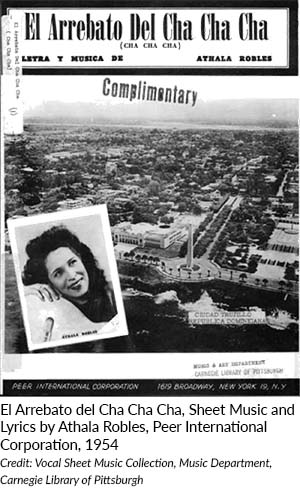

Men are not the only ones making waves during the 1940s. Two important Dominican female composers lived in the United States during the 1940s: Mercedes Sagredo de Sánchez and Athala Robles Cestero. Sagredo, trained under René Rodriguez and Dr. América Baliño,[7] and with her husband owned El Prado, a restaurant in New York City. [8] Her songs “Mi Quisqueya” and “Del Burro al Subway (click here to listen)” exemplify the immigration-related themes that Dominican artists in the U.S. had begun to incorporate into their work since the 1930s. Athala Robles Cestero, for her part, was the only Dominican musician under contract at Caribbean Music Inc., a publishing company active in the 1940s (click here to listen).[9] Robles Cestero’s voice could be heard across the nation through NBC radio, while news about her appeared in Spanish language publications in New York City.[10].

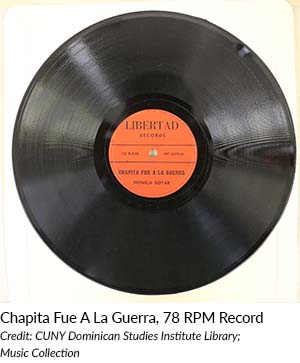

Mónica Boyar, a then famous (though now largely forgotten) New York Dominican cabaret vocalist and actress, had an active career in the 1940s, singing in nightclubs throughout New York City. Boyar moved to the U.S. in 1928, at the age of six, and unlike most immigrants and non-white artists, she did not find her artistic career segregated to uptown clubs. She actively participated in the city's nightlife and appeared in one Broadway play in 1948.[11] In the early 1940s, she performed at World War II benefit shows in Washington, D.C., and recorded Dominican folk music for the Library of Music of the World.[12]

In addition to her musical career, Boyar, an active member of the anti-Trujillista movement in New York City, participated in the struggle to overthrow dictator Rafael L.Trujillo. Her husband Federico “Gugú” Henríquez Vázquez served in the U.S. Navy during WWII and was captured and assassinated by the dictator’s military during the 1949 Luperón Expedition, that attempted to overthrow the regime. After Henríquez Vázquez’s death, Boyar would go on to record two anti-Trujillista songs “Santo Domingo (click here to listen)” and “Chapita fue a la guerra (click here to listen)” in the late 1950s.

By the end of the 1940s, increased access to recording contracts and the popularity of the mambo dance craze had bolstered opportunities for many Dominican musicians in New York City. Where earlier arrivals played in trios or recorded the occasional merengue in the studio, the era's vibrant nightlife eventually enabled talented Dominican musicians to play in more elite ballrooms. In the following decade, New York's merengue scene would benefit from increased recording opportunities and, would find its way to Latin America from the streets of New York City. This circulation of music, of course, was part of a larger context in which commodities and ideas from the U.S were increasingly penetrating Latin America and the Caribbean, particularly after WWII.

[1] Ramírez-Peralta, José G. Songs and Dances of the Dominican Republic: Twelve Compositions. New York: Alpha Music, 1940.

[2] Also billed as Petitón y sus Muchachos Cubanos.

[3] Coopersmith, Jacob Maurice . “Music and Musicians of the Dominican Republic: A Survey Part II.” The Music Quarterly, vol. 31, no.2, April 1945, 226.

[4] Currently the Organization of American States

[5] Brooklyn Eagle, September 19, 1948, 30.

[6] El Diario de Nueva York, December 11, 1948, 7.

[7] René Rodríguez, a concert soloist and a fellow Dominican, had trained at Juilliard. America Baliño was a Cuban music teacher in New York.

[8] The son of music composer José Rufino Reyes y Siancas, who composed the music of the Dominican national anthem.

[9] “Joe Davis presents Caribbean Music Inc.” The Billboard, vol. 58, no. 30, July 27,1946, 23.

[10] Revista Teatral, June 7, 1947, 12.

[11] Summer and Smoke, which opened at the Music Box Theatre on October 6, 1948.

[12] Tatar, Ben. “Boyar, Monica (1920).” Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia, edited by Vicki L. Ruiz and Virginia Sánchez Korrol. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006, 94-95.